SUBURBAN, 2011 – 13

Site-specific architectural interventions, photography, film, sculpture, and exhibition work

SUBURBAN, a series of seven architectural interventions, eleven photographic works, artifacts, and a 3-channel film work, was created over a three-year period throughout the United States, including sites in Ohio, Detroit, Alabama, New Jersey, and New York. The work was created and developed in collaboration with film crews, local volunteers, cities, land banks, and community organizations, resulting in seven architectural interventions incorporating suburban homes. SUBURBAN was conceived as an interrogation of the icon of the American suburban home, working with homes which both referencing the familiar suburban topographies of Levittown and the popular image of the American postwar middle-class home.

Beginning in early 2011, SUBURBAN was created in the shadow of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, and the economic realities of the subsequent subprime mortgage crisis. Many of the homes in this series faced demolition following foreclosure. Each intervention and site required the development of bureaucratic and community partnerships, which, after consultation, saw the external restoration of each home and the creation of the intervention, alongside the subsequent photographic and film works. This process involved large teams and community volunteers, with the photographic and film process often involving shutting down the streets for lighting and film equipment through the night and into the next morning. Developed over two years, the BURN series works within SUBURBAN resulted from collaboration with the local community in Akron, Ohio, and a local fire training academy.

The eleven photographic works, a 3-channel film work, sculptural artifacts, drawings premiered in a solo exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV), Australia in 2013, and in another solo exhibition in June of 2016 with New York-based arts organization Standard Practice.

Photographic Works

Collingham Drive, 2012

Archival digital print, 101.6 × 152.4 cm (40 × 60 inches)

Documentation of site-specific intervention

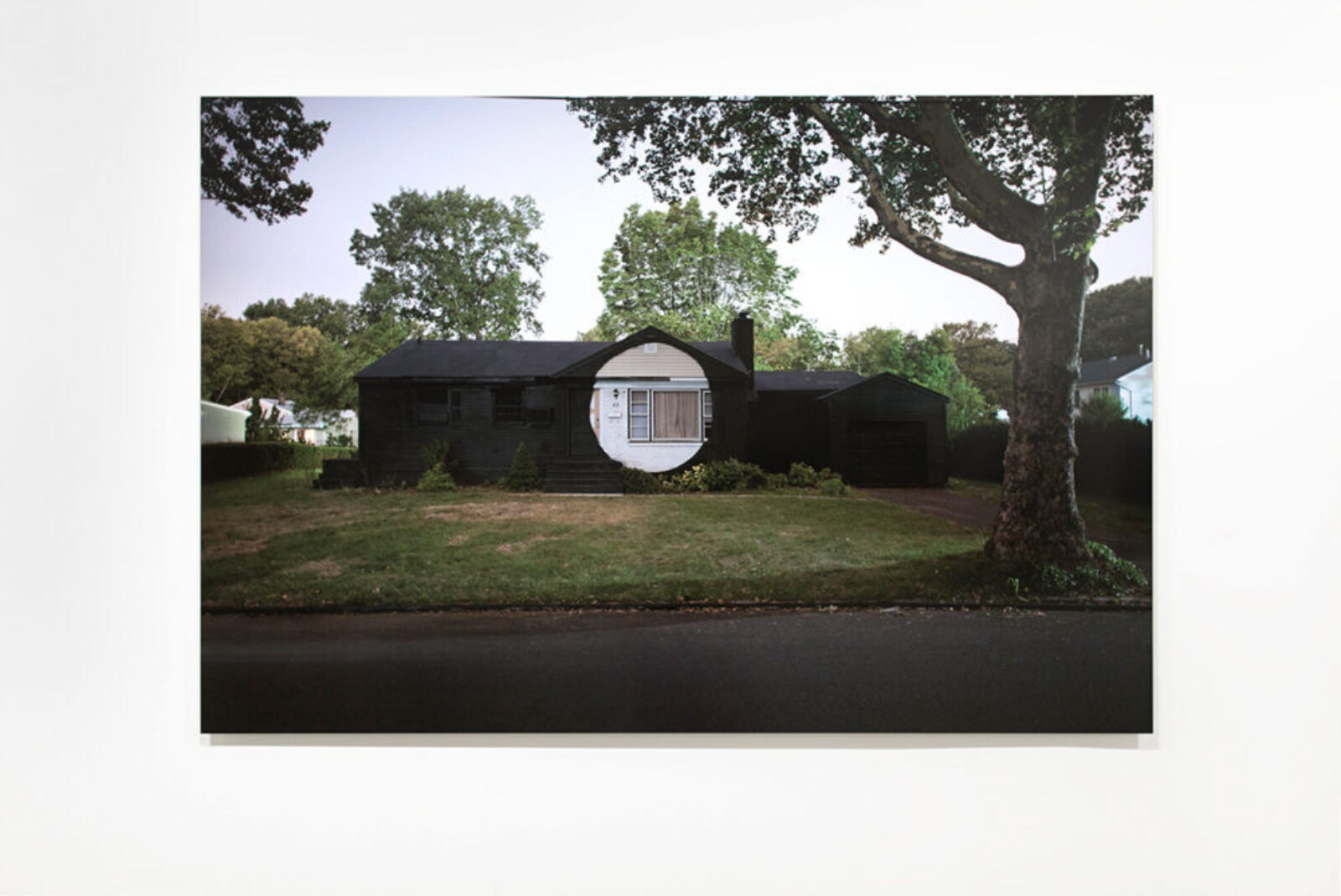

Corrinne Terrace, 2011

Archival digital print, 101.6 × 152.4 cm (40 × 60 inches)

Documentation of site-specific intervention

Avon Road, 2013

Archival digital print, 101.6 × 152.4 cm (40 × 60 inches)

Documentation of site-specific intervention

Lake Road, 2012

Archival digital print, 101.6 × 152.4 cm (40 × 60 inches)

Documentation of site-specific intervention

Harvard Street, 2012

Archival digital print, 101.6 × 152.4 cm (40 × 60 inches)

Documentation of site-specific intervention

Burn Series

Burn 2, 2013

Archival digital print, 81.4 × 122 cm (32 × 48 inches)

Documentation of site-specific intervention

Burn 3, 2013

Archival digital print, 81.4 × 122 cm (32 × 48 inches)

Documentation of site-specific intervention

Burn 4, 2013

Archival digital print, 81.4 × 122 cm (32 × 48 inches)

Documentation of site-specific intervention

Burn 5, 2013

Archival digital print, 81.4 × 122 cm (32 × 48 inches)

Documentation of site-specific intervention

Film Work

Exhibition

Writing

ESSAY: 'Ian Strange: SUBURBAN'

by David Hurlston and Polly Smith

Originally published by the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV), June 2013

ESSAY: 'Ian Strange: SUBURBAN'

by David Hurlston and Polly Smith

Originally published by the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV), June 2013

Ian Strange: SUBURBAN

by David Hurlston and Polly Smith

'Suburban is based around eight site-specific works which I have undertaken over the past two years. These involved directly painting over homes or, in some cases, burning them to the ground. These works were all meticulously planned and then documented through film and photography, working with a large film and production team.’

Ian Strange’s artistic career began when he was a teenager growing up in the suburbs of Perth, and from the late 1990s played an active role in Australia’s street art movement. Strange is now an internationally recognised artist who lives in both the United States and Australia, and more recently his art has explored notions of home and identity.

Since 2011 Strange has been working with a film crew and volunteers at locations across the United States to create and record eight site-specific interventions incorporating suburban homes. The documentation of these artistic actions, in both moving images and still photographs, forms the basis of Ian Strange: Suburban at NGV Studio. The large-scale photographs, three-channel video work and sculptural installations included in the exhibition present a powerful commentary on contemporary human habitation.

Suburban builds on a previous work, Home, unveiled by Strange in 2011, during a brief visit to Australia, as part of the Outpost festival held on Cockatoo Island, Sydney. Home was a major installation project featuring a meticulous full-scale reproduction of Strange’s childhood home (with a photorealistic skull painted over the exterior of the front room), as well as video and a performance involving the destruction of three Holden Commodores. Strange has said of the project:

‘I knew I wanted to make a large-scale work that acted as a multi-layered homecoming: coming home, building my home and investigating those origins. I also hoped that it would act as a broader work about the Australian suburbs and the feeling of social detachment and dread that I always felt was an unspoken part of their DNA … The house was built from my memory of it as an early adolescent. I began by creating a series of sketches and then eventually worked with an architect and builder to get the design right … The experience of making it was something that took me a long time to digest. I had a very surreal experience of time compacting in on itself, standing at the front door of my old house in Perth, in reality a rebuilt memory of that house, looking across the veranda out into the Turbine Hall on an island in Sydney.’

When Strange returned to the United States he continued his exploration of these themes in the current series of works. However, where Home began as a personal excursion to and review of his past, this new work has evolved to take a more universal look at urban living and, in particular, notions of the family abode and its place in contemporary Western society. The artist explains:

‘Suburban was the natural progression from the Home installation, expanding to become a much larger investigation into suburbia and the iconic role of the family home. It’s my hope that the documentation of this work allows each house to sit suspended outside a specific time or place; that the painting as well as the documentation elevates an image of static suburban architecture into something much more, so the reaction is to the icon of the home, not to the specific house.’

Strange’s two-year preparation for Suburban took him on a journey through middle America – through the states of Ohio, Michigan, New Jersey, Alabama, New Hampshire and New York. In addition to the houses featured in the exhibition, the individuals and communities Strange came into contact with have informed and contributed to the finished works. Some of the houses he worked on were made available as part of a program to reinvigorate local communities through creative contributions by artists. Other houses, located in more economically depressed areas, had been abandoned, and others again were going to be razed to enable land to be released for redevelopment:

‘It was absolutely the biggest and most difficult project I have ever taken on, especially when you are trying to convince neighbourhoods to allow you to set up lighting and film equipment and to shut down streets in order to paint an entire house or set it alight. But the crew I had were amazing and we found incredible support from local teams in each city, including volunteers, other artists, community groups, film crews and fire departments.’

Strange has used a number of techniques and processes as part of his exploration, from spray-painting images directly onto facades to repainting entire houses in monochromatic colour schemes, transforming them from places for living into enormous and highly charged sculptural objects. The most dramatic of all his approaches, however, are the two cases in which, with the involvement of the fire department, houses were set alight and burned to the ground in an act of symbolic requital; the surviving record of their existence being Strange’s art-directed photographic and film documentation.

Suburban is a powerfully evocative and compelling body of work. Strange’s photographs and videos challenge the idea of the family home as a place of warmth and safety by simultaneously elevating and destroying it, both literally and figuratively. In doing so, Strange reveals his own antithetical relationship with the suburbs and invites us to explore our own response to them. As he says:

‘I have always had a conflicted relationship with the suburbs and I can draw links in this work all the way back to myself as a teen in the suburbs of Perth. I feel I’m still asking a lot of the same questions I had then, but also as someone who has left and is looking back. How we understand home is a very personal thing, so I expect people will bring their own very specific experiences to the work – I’m very interested to see the reactions, good or bad, and for them to also help my own understanding of the work.’

—

Originally published by the National Gallery of Victoria, July 24, 2013 on the occasion of Ian Strange: SUBURBAN solo exhibition, 26th July – 15th September, 2013 : The Ian Potter Centre, National Gallery of Victoria (NGV)

David Hurlston is Curator, Australian Art, at the National Gallery of Victoria. He is the curator of Ian Strange: SUBURBAN at the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV).

ESSAY: 'From Home To Home'

by Sarah Crown

Originally published June, 2016

ESSAY: 'From Home To Home'

by Sarah Crown

Originally published June, 2016

From Home To Home

by Sarah Crown

Many artists have worked on the concept of home but few have used the house as a physical medium. Names that we can recall immediately are Gordon Matta-Clark, Rachel Whiteread, Louise Bourgeois. Their monumental creations with or on houses have effectively changed the way in which we think about the home as a symbol and stretched our concepts of public art and sculpture. The importance of their work lies not only in the implication of a huge physical effort but also in a new way of documenting it. Their influence on the younger generation of artists is still strong, but the uniqueness of their work continues to stand alone.

Ian Strange is one of very few contemporary artist whose main medium and preoccupation is the common suburban house. Not a specific one, but a very general one. One of those houses that doesn’t speak about its social, political, or cultural context, but instead is just a house. Or better yet, a home.

He investigates home as a place of safety and security, a place of identity, privacy, and understanding. Born in Perth, Australia but now working and living in New York, he left his personal home in search of a new one. Whether he has found it yet is uncertain, but his search has led to a large body of work about the possibilities that a house—a home—can offer.

Strange’s artistic practice first turned to these themes with the installation Home (2011), a site specific installation in the turbine hall on Cockatoo Island, Sydney. Strange built a full-scale replica of his childhood home from early adolescent memory and installed three destroyed Holden Commodore Cars, the ultimate symbol of average Australian suburban life. Inside the home, a video and sound installation documents Strange destroying the three vehicles, effectively rejecting the “suburban angst” he experienced growing up in the suburbs of Perth.

As a receptacle of hope, grief, desires, secrets, life, and inevitably death, the house represents more than a visual encounter with the artist’s childhood; the house appears to the viewer like Theodor Fontane’s novel Effie Briest (1) to the reader: an idyllic place at first sight that conceals a lurking element of threat. The romantic and blithe atmosphere that opens Fontane’s book nevertheless hints at the tragic ending of the novel’s protagonist. In Strange’s work we have a similar situation: the idealized garden entrance leads to the sunny façade of a house decorated with graffiti of a fading skull, insinuating fear, insecurity, and death. Indeed, the installation bears reminders that stability is an illusion, a deceit. The viewer is exposed to the feeling of unease “that is concomitant with the sublime feeling that one is levitating on the lip of the abyss. In Strange’s work, the abyss is the suburban.”

His subsequent series titled Suburban explores similar themes, expanding the concept from a personal level to more universal one. Two years of work with a film crew and volunteers in Ohio, Detroit, Alabama, New Jersey, New York, and New Hampshire made it possible to create, photograph, and film eight site-specific interventions on real suburban homes.

From this series, Corrinne Terrace (2011) is a large house in Mountainside, New Jersey entirely painted in black except for a large circle in the center. The geometric form functions like a peephole into the home, emphasizing the entrance door and the experience of entering a familiar space that evokes belonging and warmth. As in other of his works, Strange situates the house as the focal point of a film set. Through the lens of the camera, the viewer is able to investigate, with high cinematographic quality, the exterior and interior nature of the home. With the appearance of dusk in the film, the entire building merges with the surrounding landscape and slowly disappears into the darkness, leaving visible only the bright circle.

Strange made a related intervention a year later with Lake Road (Avon Lake, Ohio, 2012), but here he turned the farmhouse red from bottom to top. The building appears cartoonish and unrealistic, displaced as if fallen from the sky. The now artificial-looking house, exaggerated even more in contrast to the surrounding natural landscape, is alienating. Windows are shut, doors are closed—no sign of life is around. In 2013 he repeats the same concept with the color black on a house on Avon Road (Avon, Ohio, 2012). The house, which completely disappears once the sunlight vanishes, looks big, sad, and dark, abandoned and menacing and like a void in the landscape.

Other houses have been marked by Strange with simple geometric forms like circles and crosses. The facade functions as a canvas, but instead of painting characters or visual tales, the artist opted to mark them with a big black dot or to cross them out in red, like symbols in a board game. The acts involved in making this body of work lie in both the physical intervention on the house(s) and the documentation of it. Similar to Gordon Matta-Clark’s well known work Splitting (2), the artist strained himself in the transformation of the facade and structure into a subject of photography and film. Both artists removed through their physical act the debris of habitation from the houses by erasing any quality of home, but while Gordon Matta-Clark’s work was a reflection upon the growing divide between the middle class and the wealthier suburbs, casting the cut house as a metaphor for the social, cultural and architectural context, Strange turned the house into an icon of suburbia, emptied of any personal meaning— representing a universal idea. The artist’s intention was not to decorate these houses, nor to tell their individual stories. He rather sought to remove them from their conceived function. What was once an intimate place for living and sharing becomes a monumental sculpture of public access.

The project Suburban culminates in two houses getting burned to the ground (in collaboration with the Cuyahoga Fire Training Department). Nothing is left except ashes and the smell of burned belongings and construction materials. By erasing the buildings through this ultimate act of devastation, the artist tries to requite his own difficult relationship with the suburbs, the bourgeoisie, the constraints of a small town.

Strange’s monumental interventions exist on two extremes of the spectrum of destruction and of elevation. By doing so he challenges our understanding of home and safety. He erases place and time, playing with the tensions between inside/outside, real/unreal, alive/dead, which increasingly intensify in his video works: three-channel film installations that draw the viewer into an emotional journey. While the central camera makes a direct trajectory towards the entrance of the house, the two lateral videos focus on details of the surroundings: objects that refer to the inhabitants, parts of the neighborhood and garden nooks, or simply nature’s forces like rain, wind, sunlight. The slow-moving camera, the focus on minute details, and the gathering score envelop the viewer in a construction that feels akin to a crime scene. The alienation of house from original function, the building’s visual elements, and ultimately the blazing fire produce a contrarily sweet, hypnotic effect that explores the psychological aspects of each place without being specific to the former inhabitants.

The body of work that Strange created between 2011 and 2013, following his personal questions about belonging and idealized local architecture, is huge and powerful. It took him on a journey through middle America where he was in direct contact with individuals and local communities. Some of the houses he worked on were made available as part of a program to reinvigorate local communities through creative contributions by artists. Other houses for his projects, located in more economically depressed areas, had been abandoned with plans, in some of cases, to be razed for redevelopment.

In his subsequent series Final Act (from 2013 onwards) Strange empties and dismantles houses completely, keeping only the skeleton. Number Twelve, Number Thirty-Nine, and Number Thirty-Four, for example, are three of 8,000 houses in Christchurch, New Zealand in the derelict suburb of Avonside, the heart of an earthquake red zone. The government’s Earthquake Recovery Authority gifted Strange with a series of houses that he stripped of all personal references. He then filled them with white, cold neon light. By illuminating from the inside, he transformed the houses into huge glowing sculptures, emphasizing the structure as fundamental, emotional elements in our lives. The resulting photographs and video works represent at the first sight an encyclopedia of houses and urban landscapes. Like in the pictures of Bernd and Hilla Becher (3) Strange reinforces the structural properties of the architecture, yet he is not interested in determining their function or in finding any common quality. His main interest lies in determining new parameters for architecture and suburban aesthetics, not to create a dictionary of it. The theatrical scenes create a barrier between the viewer and the subject, between the desire to look at and the ambiguities inherent in the unease of witnessing destruction. The lack of descriptive elements (the removed belongings) bar any possibilities of empathetic resonance, but the transformation of these houses into beacons before their demolition invites a cathartic emotional response. His works stand at the opposite end of the spectrum to the Cells (4) of Louise Bourgeois, which work exactly on those ‘emotional aspects and psychological microcosms that the personal objects inside a home can create.’

Ian Strange demonstrates with his serial interventions and focus on creating icons rather than a catalog, a completely new way of dealing with the house, with urban architecture and ultimately with the idea of home as a safe and definite place. By avoiding any form of categorization he shows his antithetical relationship to the suburbs opening to a vision of our places of abode that is new to our cannon of understanding. Strange can therefore be called not only a successor of the artists cited in this essay, but also the author of a new genre.

—

This text is published on the occasion of the exhibition Ian Strange: SUBURBAN, May 20- 31, 2016, 136 Bowery, New York NY.

Footnotes:

(1) Fontane, Theodor, Effie Briest, Leipzig (DE), Philipp Reclam jun. GmbH & Co. KG, 1896. Print.

(2) Matta-Clark, Gordon, Splitting, 1974, Site-specific intervention, Englewood, New Jersey.

(3) The J. Paul Getty Museum, Bern and Hilla Becher, online archive: http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/artists/1777