Excerpt from SHADOW, 2015

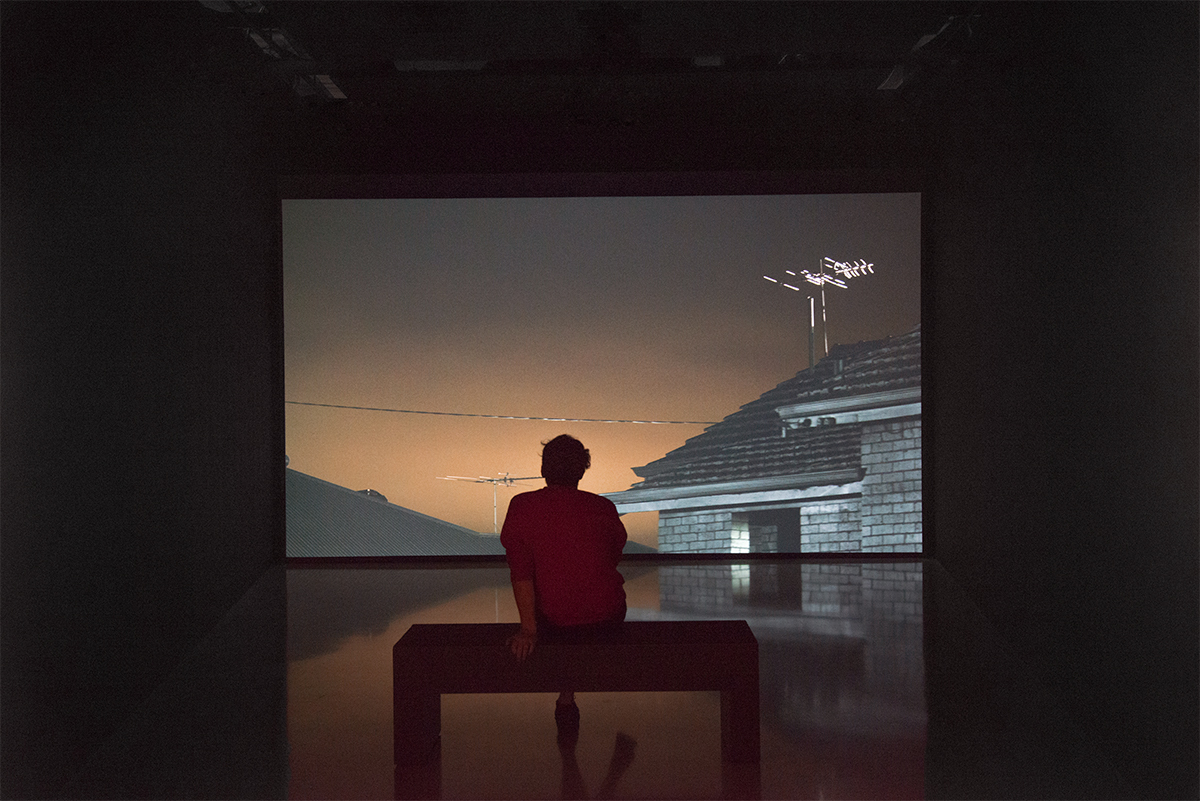

Single channel film, 2k digital, 16:9, 5.1 surround sound.

SHADOW, 2015 – 16

Site-specific architectural interventions, photography, films, and exhibition work

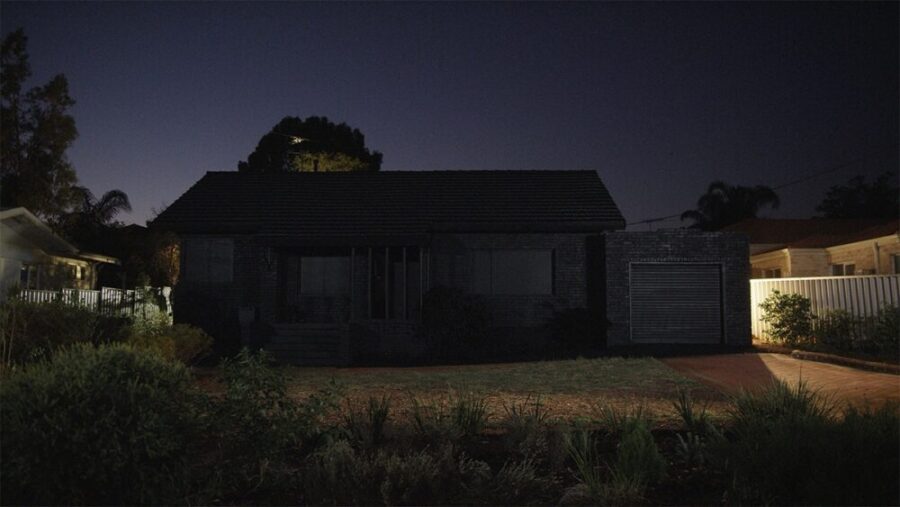

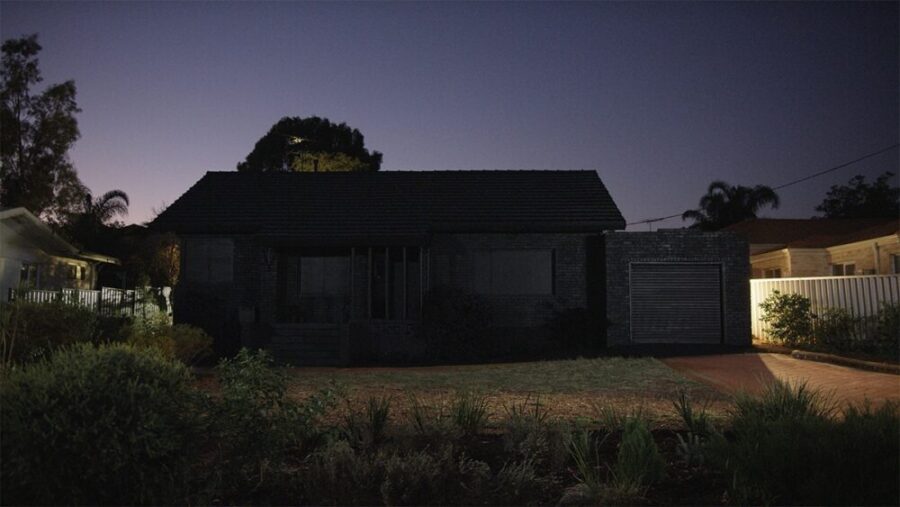

Created between 2015 and 2016, SHADOW comprises two single-channel film works, and five photographic works incorporating site-specific interventions onto post-war Australian red-brick suburban homes. A ubiquitous feature of Australia’s post-war residential landscape, SHADOW responds to these archetypal homes as a powerful symbol of post-war aspiration, and to the cultural forces they continue to represent.

In the March 2017 issue of Art Almanac, Craig Malyon wrote of SHADOW:

“In creating and documenting these house interventions Strange transforms these iconic red-brick Australian homes into a void etched out of the landscape. Symbolically erasing the homes with black paint and rendering the familiar architecture unfamiliar, questioning them as an icon which has informed so much of Australia’s national identity and subsequently obscured a deeper history.”

The interventions created with these homes for SHADOW were at the height of a generational economic boom fueled by the mining industry in Western Australia. This created record housing prices, dramatically increased land values, and consequently left many of these formerly affordable post-war homes slated for demolition. Following research and development of each work, the interventions for SHADOW were created working with a large local team of collaborators, a film crew, and volunteers. This saw each home restored, with the interventions created using matte black paint to symbolically and visually cast the homes into shadow. Over a period of three weeks, the works were filmed and photographed at night, alongside site audio recordings, and a month of additional studio-based film shoots for the accompanying single-channel film work.

SHADOW premiered as an eponymous solo exhibition at the Public 2015 festival in Western Australia and a solo pop-up exhibition in 2016 for Art Month, Sydney, with the support of the Australia Council for the Arts, the Department of Culture and the Arts Western Australia, and arts organisation FORM.

Photographic Works

One Hundred and Ten Watkins, 2015

Archival Digital Print

Selected photographic work from SHADOW

Three Hundred and Nine Wannaroo, 2015

Archival Digital Print

Selected photographic work from SHADOW

Twenty-Four Watkins, 2015

Archival Digital Print

Selected photographic work from SHADOW

Sixty-Two Wasley, 2015

Archival Digital Print

Selected photographic work from SHADOW

Seventy-One Langley, 2015

Archival Digital Print

Selected photographic work from SHADOW

Film

Film Work: 'Shadow'

Film Work: '71 Langley'

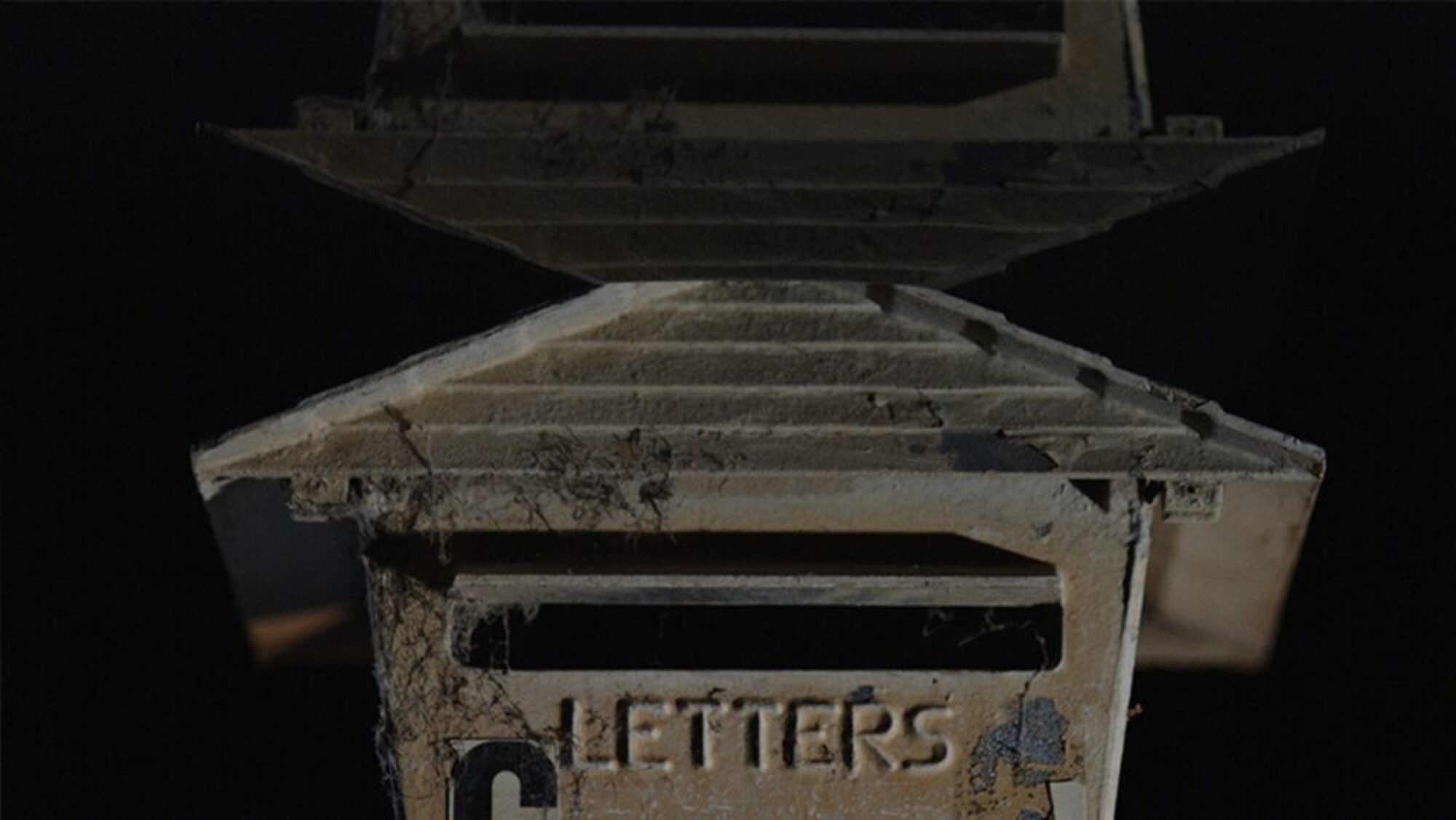

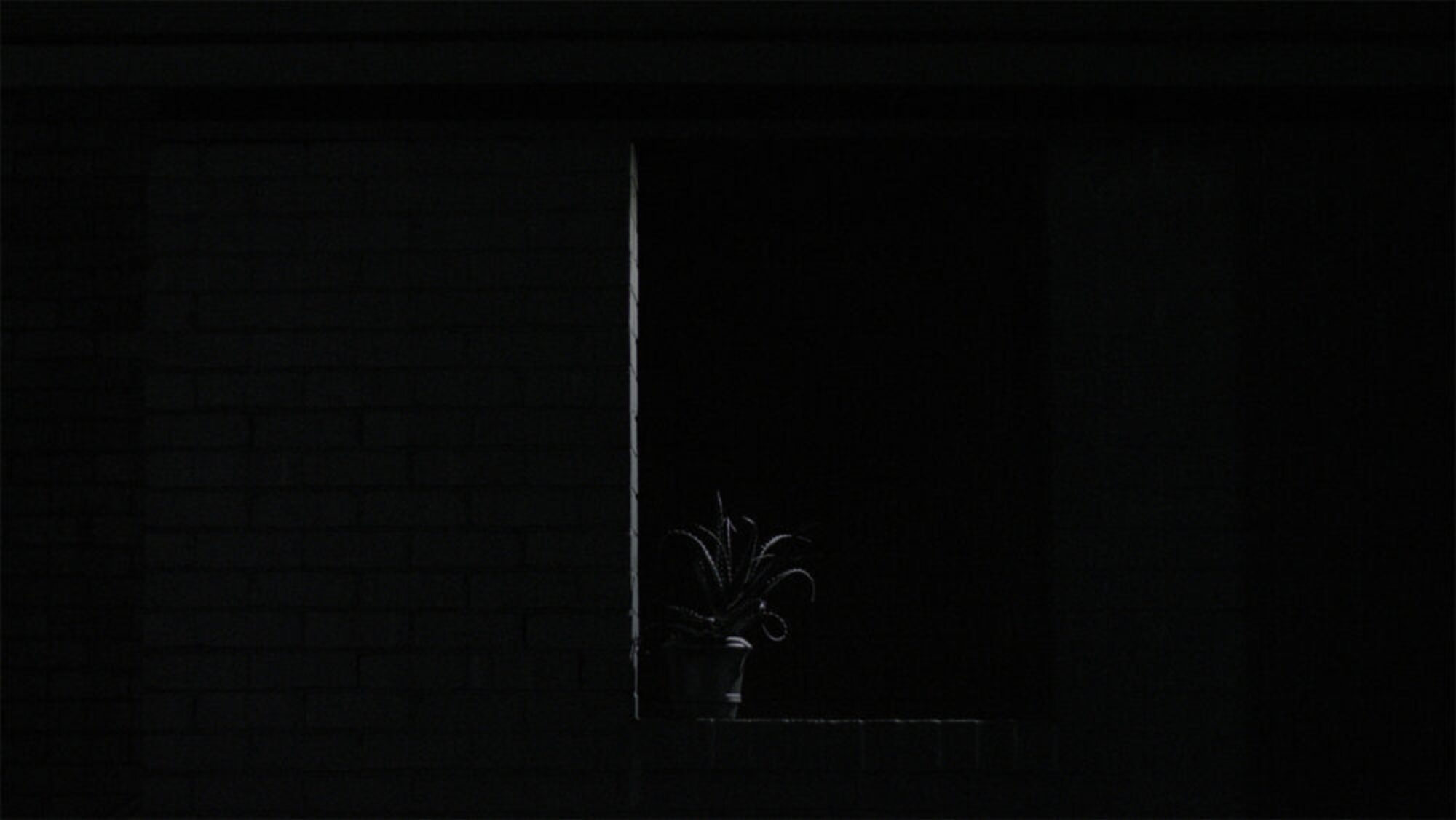

Still frames from 71 Langley, 2015

Single channel, 4k digital film, 16:9

5.1 surround sound 34m20s duration, Looped

Exhibition

Writing

ESSAY: 'Ian Strange’s Shadows of Home'

by Kate Britton

Originally published March, 2016

ESSAY: 'Ian Strange’s Shadows of Home'

by Kate Britton

Originally published March, 2016

Ian Strange’s Shadows of Home

by Kate Britton

Ian Strange only began making work about the idea of home once he had left his behind. The move from the suburbs of Perth to New York was a productive one, affording Strange the opportunity to critically reflect on where it was he came from. In 2011 he was invited back to Australia to produce a large-scale installation on Cockatoo Island, an indigenous fishing port turned convict penal establishment turned shipyard turned art venue in the centre of Sydney Harbour, and the cavernous Turbine Hall, hundreds of metres squared and several stories high, became the site of Strange’s first significant piece of work about home.

The aptly titled HOME was a full-scale replica of the artist’s childhood home, built from memory and populated with a video work showing three exploding Holden Commodores, the ruined shells of which were lined up outside the house on the ghostly lawn. It was an uncanny image; an almost perfect replica of a commonplace suburban house, flung out of space on an island that from what anyone can tell has only ever been inhabited by convicts, criminals and adolescent girls deemed in need of ‘reform’ – all distinctly un-suburban characters exiled to an island in the middle of the city.

In the 2015 series SHADOW, Strange returns to the suburbs of Perth, bookending a series of projects that took him to the suburbs of America at the apex of the subprime mortgage crisis; the residential ‘Red Zone’ of Christchurch following the 2011 earthquake, where some 16,000 houses were slated for demolition; and to Australia once again for the 2014 Adelaide Biennial, for which Strange deposited a full-scale three-bedroom house outside the sandstone Art Gallery of South Australia as if it had dropped from the sky.

SHADOW is a series of five large photographic works and a film work. Classic Western Australian red brick suburban homes have been painted entirely in black and images captured front-on, flanked by similar single-story brick homes, on a backdrop of interminably blue sky and inevitably scrubby lawns, hard won in the desert heat. The images are monumental and surreal, as strange as, and deeply connected to, our compulsion to plant green manicured lawns on the dry red dirt of West Australia, one of the most extreme climates in the world. In this sense, Strange’s work could be read as a sort of poetic warning to the Australian dream, in the way some people claim Stonehenge or the Great Pyramid as warning of some future catastrophe.

In the series SUBURBAN, created in suburban America between 2011 and 2013, houses have been similarly intervened on – painted with crosses and circles, painted all in red, set on fire. Produced amid the crashing GFC housing bubble, an environment of mass foreclosures and mortgage defaults, a new American bad dream. This is the story of a time and place, during which things that seemed solid suddenly crumbled as the world looked on.

By contrast, the images in SHADOW evoke a murkier panic, like that experienced in deep water. What disaster has befallen these houses and their residents? The images seem unreal and yet they are not; they are deeply familiar and unnerving at the same time. Accompanied by the film work, a slow abstract panning over a blackened home in which we see parts but never the whole of the dwelling, SHADOW plays unapologetically on our memories of home. Indeed, the choice of houses in these works is no accident; the archetypal red brick homes of the post-war austerity era are an iconic image for many Australians, one that speaks to dreams of a better life, a home for all.

Memory has always played a big part in Strange’s work. In HOME, it was his own memories that most informed the project, plumbing them to replicate his childhood home. As the body of work progresses however, this focus begins to expand – from the memories of others in projects like SUBURBAN and FINAL ACT (the New Zealand works), to some other sort of memory, a more intimate and universal sense of home, in which home becomes as much an idea as a place. In these gestures towards the abstract, Strange reveals his fondness for Bachelard and the phenomenologist’s seminal text The Poetics of Space. There is an oft-quoted line in the book that reads, ‘the house shelters day-dreaming, the house protects the dreamer, the house allows one to dream in peace’. The house is an intimate space; it shelters our most vulnerable selves, and it is this sense of protection and comfort that Strange’s work takes up, uses, cracks open and inverts.

By painting directly onto these iconic homes, Strange etches a void into the landscape, rendering these most familiar of spaces surreal and unfamiliar. Stripped of any of the interior markers of home, these houses become impenetrable objects, intruders into a landscape that remembers a different history. Viewed through Strange’s eyes, the suburbs look as jarring as they are, dreams imported from somewhere else, often in direct conflict with their environment – red brick houses a simulacra for the red dirt they sit atop. What is lost when a house or a suburb is gained?

A sense of loss plays out across much of Strange’s work. It is too easy however, to read the work in terms of a darkness that lies beneath the promise of the suburbs; about hidden violence and false promises; the didactic aesthetic assumption that to cover something (in paint for example) must beg the question of what is beneath, what is hidden. This reading loses something of the temporal slide that plays out in these works. What if rather than ask what is hidden, we ask what is lost? In SHADOW, the black houses look almost cut out, erased from their landscape. They simultaneously gesture to our pasts, a childhood sense of the home as secure, as impenetrable and safe (if we are lucky); to our present in which we watch the promise of the suburbs falter; and to our future, in which these spaces may disappear, taken from us or abandoned by us for different dreams and competing priorities.

‘A creature that hides’, Bachelard wrote, ‘is preparing a “way out”’. In both the images and film that make up the SHADOW series, the homes seem to be hiding, whether in plain sight, via a sort of emphatic erasure, or in the abstraction of darkness and filmic close-up. In the film, Strange allows the camera to linger on minute details – the angle of a metal roof, the curl of a railing, the peak of a letterbox. These things become Proustian, madeleines teeming with an excess of emotion, meaning, memory. ‘If we remain at the heart of the image,’ Bachelard says, ‘we have the impression that, by staying in the motionlessness in its shell, the creature is preparing temporal explosions, not to say whirlwinds, of being’. In their strange stillness and uncanny emptiness, Strange’s houses seem somehow ready to burst, a promise almost literally fulfilled by the series FINAL ACT from New Zealand.

Eschewing his trademark red and black markings, Strange instead filled the houses of the earthquake zone with bright white light, making them glow from within like the slow brilliant death of a star. These images represent their subjects’ final act, a sublime celebration of the lives lived within before the earthquake, an ode to the ephemeral, emotional core of our relationship to house and home. In them, which read more readily as hopeful than their black, marked and burned counterparts, there lies a critical aspect of Strange’s work, less apparent in the rest of his home series but at their heart nonetheless. What is it that makes us respond with such unease to these images, with such a heady mix wonder and panic?

In Sceptres of Marx Derrida outlines a concept he calls hauntology, which at its most basic proposes that to understand something, we must understand what haunts it, the unseen and unspoken thing seemingly absent yet defining a thing through its very denial.

Strange’s work is haunted by those very things it seems to deny: optimism; safety; futures; possibility. It has been said that hauntology evokes a nostalgia for lost futures, an idea that seems apt to Strange’s work. How many of us dreamed as children of one day having a home for ourselves? How many new arrivals to our country still flock to the suburbs, seeking the simple promises of the home – security, safety, a space to dream? This is the lingering hold of the suburbs, which continue to sprawl despite their failure to deliver on their promises.

If Strange’s work shows us nothing else it is that the suburban house is as vulnerable as our bodies. In spite of the vulnerability of these buildings, however, Strange’s work cannot but be haunted by optimism. What is more optimistic than building a new community and an art work in a disaster zone? The time and labour behind these projects is tangible, the stories of those who have inhabited these spaces present in the work. Our homes may crumble, be taken or abandoned, be marked and burned to the ground; but our dreams of them, our intimate memories of and connection to home, are unassailable. SHADOW is an immense body of work, both in scale and ambition, but it is also deeply personal. Perhaps Bachelard was right; ‘immensity is within ourselves’; we are all haunted by a sense of home.

—

Kate Britton is a curator and writer based in Sydney. She was a Director at Firstdraft from 2014-15, and has curated a number of independent exhibitions in spaces such as Success (WA), Firstdraft, and 107 Projects. Her writing has been published in Un Magazine, Sturgeon, Runway, Art Monthly, Art Collector, Das Superpaper, West Space Journal, and many more. She recently completed a PhD in contemporary art and politics at UNSW Art + Design.

ESSAY: 'The Aesthetics of Ruination'

by Craig Malyon

Originally published by Art Almanac, March 2017

ESSAY: 'The Aesthetics of Ruination'

by Craig Malyon

Originally published by Art Almanac, March 2017

The Aesthetics of Ruination

by Craig Malyon

"The home can represent a place of safety and security, so it depends on where the home is placed for the viewer. For me a marking on a house isn’t an act against that specific house, it’s an act against the ideas of what the home represents. It presents larger ideas of the home as societal cohesion, safety, family and community. Then there is the idea of the imagined home, the home of childhood, these poetics that we have inside us, that we carry with us.” – Ian Strange

Ian Strange’s interventions on domestic suburban houses traverse our memories. In his latest exhibition ‘Shadow’ the treatment of dwellings becomes an interlocutor of our most personal experience – ‘home’. There is an acute awareness of the emotive connection the audience has for the home and his authorisation of these images and videos become a visual register for both the familiar and mysterious. He deconstructs the ‘site’ as landscape, ‘intervention’ as medium and ‘conceptual index’ as domestic experiences in these ubiquitous structures. From his early work, akin to graffiti and street art, there has been a psychological and aesthetic shift over the years but what remains central is recognition of the vulnerability of the house.

“The symbol of the home, both real and imagined, is very important”, said the artist, “I like the idea that it is our first metaphor – how you understand inside and out, of lightness and darkness, the extension of yourself, it becomes a way of understanding of the world.”

Strange presents encounters of suburbia that are at once genuinely astonishing and seemingly archetypal. His work has always sought to extirpate obvious narratives and occupy a space within an ambiguity that both transgresses and augments the sinister qualities of suburbia. The exhibition title alludes to phenomenological motif, a stain on the landscape, an affliction to our personal memories, impairment on the utopic modern idealism of the urban sprawl and the ruined view of the perceived safety of our homes.

Ironically, to talk about the stasis of the suburbs we met in inner city Sydney. Nearby his ‘pop-up’ exhibition will be staged in Chippendale, a historic area, once industrial and unseemly, now experiencing a heavy gentrification marked by artisanal cafés, galleries to investment in high-density living. “You read the red brick house as an absurdist object that populates the desert, yet within the context of the rest of suburbia they are not absurd… the suburban home got me thinking how Australia allowed denial of the landscape and by painting them black it is an action of imaging them not there, erasing them. I think about them as negative space. As the viewer inspects the photographs they realise an action has been taken against the house. It is the action of painting the house and an implied element of performance.”

Strange knowingly plays with absurdity within the image through performative actions, that evoke a critical evaluation of the suburban house. The homes selected by Strange strike an accord with the viewer’s sense of self and place, yet remain completely anonymous, the title alluding only to the street name and not the inhabitants. For many, the suburban house instills identity (personal and social). In this series he presents a mordant realisation of suburbia in the post-mining boom of Western Australia. The red brick home comes to symbolise loss within this context. The façade (or skin) of the house presents a texture of decline and the work makes it difficult to avoid the current sense of social regression and the loss of the post war idealism that catalysed suburban housing globally. The blacking out of the houses in ‘Shadow’ absorbs the audience’s own perceptual discrimination. This void draws out a new consciousness that endows the depicted houses with their own unique subjectivity, surpassing its practical function to operate as powerful metaphor.

The marking of houses is not new and the artist is quick to point out the historical precedent from doorways during Passover to the condemnations of homes during the bubonic plague. Dwellings have been provocatively inscribed from slanderous graffiti on homes during the Nazi ghettoisation of the Jewish quarter to the pleas for help, more recently, written on the flooded houses during the devastation of hurricane Katrina in the USA. He explained “I’m interested in what the psychological shift is, how you realise the house once it has been treated this way as it attacks the imaginary boarders we draw out with our homes.”

For Strange the house evolves into its own being, residing in both a physical and psychological manner that generates its own austere transcendence of prosaic suburbia. His images are bathed in a twilight of personal enchantment and disenchantment that unwittingly reflects current ideologies tempered by dread. Look no further than to the rise of Donald Trump or the landscape of post-GFC cities. ‘Shadow’ isolates a fragment of the suburban world identified as safe and familiar to the audience, replacing it with an affectation of anxiety and an aesthetic of ruin. This ongoing global body of work from its origin in the USA and later in Christchurch, New Zealand to Australia reveals a universal currency of the ‘home’. The equivocality of ‘Shadow’ encapsulates Strange’s visual logic to make art that is compelling in its operation as personal investigations, intervening actions and psychosocial critique.

—

Craig Malyon is an educator and writer based in Sydney. The article was originally published in Art Almanac March issue, 2017

Credits

SHADOW was created in Perth, Western Australia in 2015, and was originally commissioned by FORM for the 'PUBLIC 2015' festival and symposium. It was created within a residency at the Western Australian School of Art Design and Media, and with the support of the Department of Culture and the Arts, Western Australia. The work premiered in April 2015 in the solo-exhibition 'Shadow', PUBLIC festival, Perth, Western Australia. SHADOW was produced by Amelia Philips and Jedda Andrews.

[FULL CREDITS]

Artist/Director: Ian Strange

Co-Director(film): Dominic Pearce

Executive Producer: Jedda Andrews

Producers: Amelia Phillips, Jedda Andrews

Production Assistant: Ciaran McDonald, Martine Linton

Director of Photography: Sam Winzar

Camera Operator: Dom Pearce, Sam Winzar

2nd Unit Camera Operator, Cinematography: Dom Pearce, AJ Coultier

Camera Assistant: AJ Coultier, Luke Corbett, Michael Boyle

Grip: Luke Corbett, Michael Boyle

Gaffer: Dion Borrett, AJ Coultier

Lighting Assistant: Luke Corbett, Michael Boyle

Head of Art Department: Emma Vickery, Will Heerey

Editor: Dominic Pearce

Colourist/VFX/Post Production: Dominic Pearce

Editor Assist - Data Wrangler: Elaine Smith, Luke Corbett

Score: Marc Earley

Research: Christina Chau

Behind the Scenes Photographer and Videographer: Elliot Strang, Lloyd Subber, Jedda Andrews, Trish Prinsloo, Courtney Matthews

Artist Assistant/Art Department Assistant: Michael Cuellar, Ross Mills, Gavin Mulroy, George Howlett, Reegan Jackson, Nick Zafir, Bruno Booth, Georgia Shepherd, Korrin Stoney, Zane Lingard, Kalem Bruce, Yolanda Azis, Helena Waldmann, Ben Byrne, Reid Smith, Courtney Matthews, Michael Boyle, Luke Corbett, Alex Lorian, Abel Feleke, Hannah Davies, Brad Serls.

SPECIAL THANKS:

Public festival, FORM, Paul Chamberlain and family, the Department of Culture and the Arts, Western Australia, Central TAFE, and the residents, home-owners, and communities of East Perth, Fremantle, South Perth, and Innaloo.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF COUNTRY:

The artists and producers of this work acknowledge the unceded lands upon which SHADOW was created, and from which we work, the traditional land of the Beeliar people of the Whadjuk Noongar clan. We pay respect to First Nations Peoples as the first artists and storytellers to walk this Country and acknowledge their continuing connection to land, waters, and culture.