ISLAND, 2015 – 17

Site-responsive architectural interventions, photography, film, studio works, research and publication

ISLAND utilizes sculpture, research, found artefacts and drawings, and is anchored by three major photographic works, which document interventions undertaken directly onto suburban homes in the USA. The work includes new research and work created in Ohio, Detroit, and New York between 2015 and 2017.

The project title and the texts applied to the houses suggest the metaphor of a desert island, a place connoting both personal sovereignty and entrapment (“SOS” written in the sand), as well the history of marked homes in situations of crisis. ISLAND simultaneously reflects on the individual circumstances of the selected homes and on the identity of the house as both vulnerable object and personal vessel for memory, selfhood, and aspiration.

In his catalogue essay ‘Island’ Sreshta Rit Premnath writes,

“The complexity of Ian Strange’s ISLAND lies in the balance it strikes between the socio-political realities that dictate who owns a home and who cannot, as well as the psychological experience of memory, longing and loss that we all carry with us through our lives from one home to the next.”.

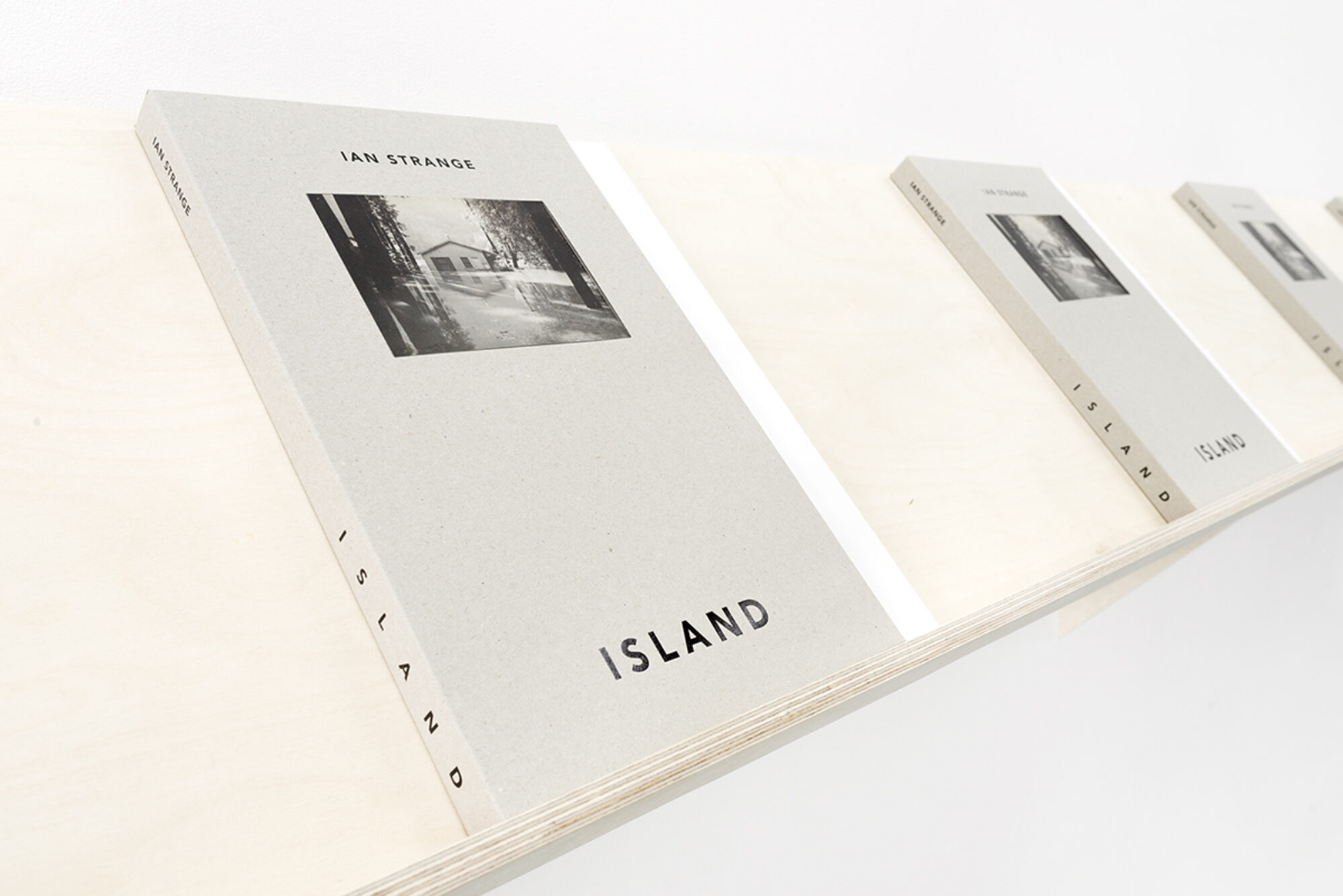

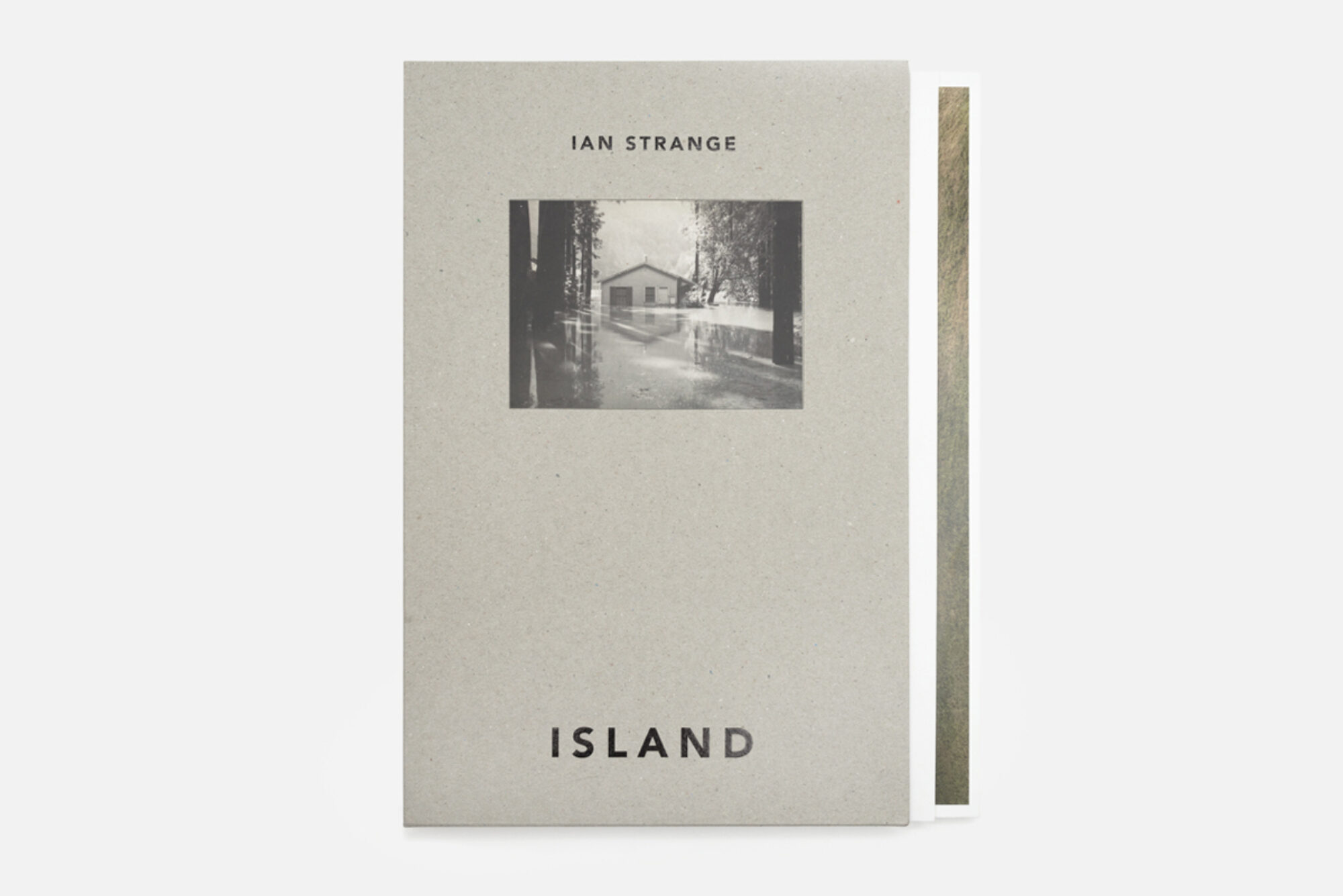

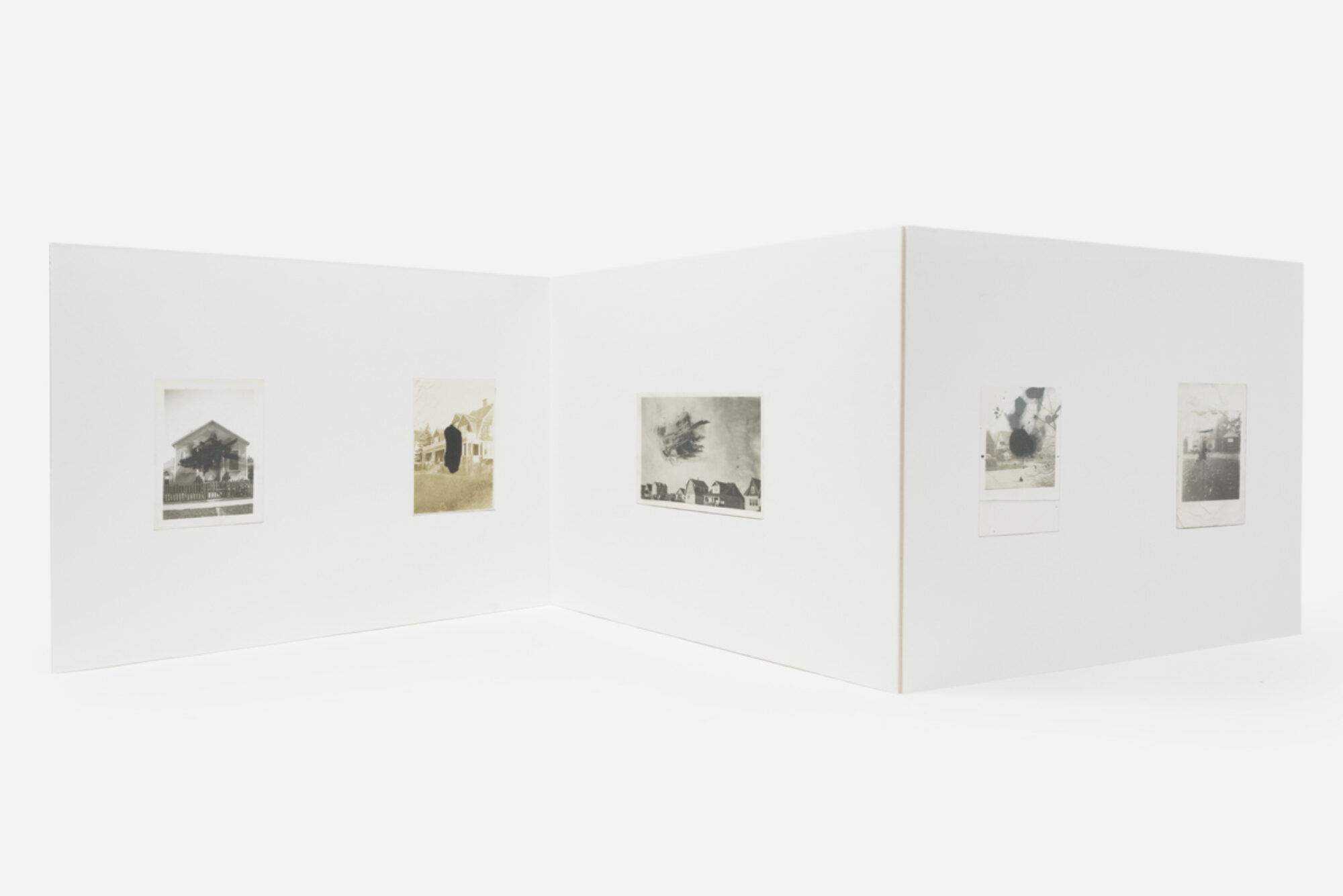

The research materials, found objects, and drawings that inform ISLAND, alongside the three anchoring photographic works, constituted solo exhibitions at FAC (Fremantle Arts Centre) in Australia from July 22 to September 16, 2017, and in New York City at 149 West 14th St. by arts organisation Standard Practice from November 18 to December 16, 2017. An accompanying publication, 'ISLAND' was released in partnership PAMPAM press in late 2017.

Photographic Works

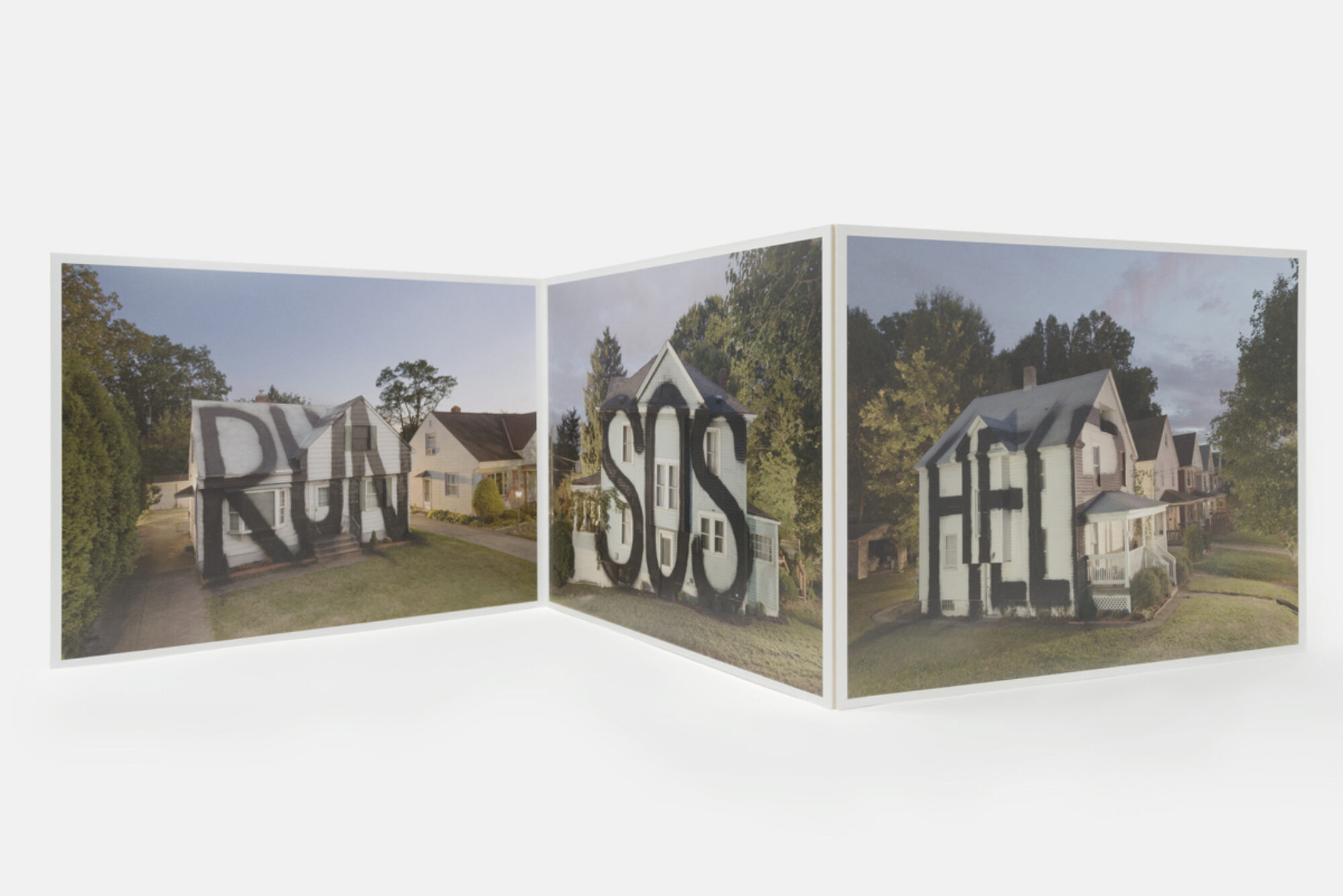

SOS, 2015

Archival digital print

Documentation of site-specific intervention

HELP, 2015

Archival digital print

Documentation of site-specific intervention

RUN, 2015

Archival digital print

Documentation of site-specific intervention

Exhibition

Publication

Writing

ESSAY: 'Island'

by Sreshta Rit Premnath

Originally published by FAC, November, 2017

ESSAY: 'Island'

by Sreshta Rit Premnath

Originally published by FAC, November, 2017

ISLAND

by Sreshta Rit Premnath

The culmination of a two year long project in Ohio and New York, Ian Strange continues his ongoing exploration of the contradictory ways in which the idea of home signals both safety and entrapment. The exhibition’s title, ISLAND conjures the image of shipwrecked sailors taking refuge on dry land, and conversely–in light of recent natural disasters–people trapped and confined with no escape.

In his photographs, sculptures and installations Strange uses an iconic signifier of home, the American suburban bungalow, with its pitched roof construction, that is designed to visually reinforce the ideal of a self-sufficient, middle-class, nuclear family. It is invested in the idea of independence, and is typically separated from surrounding homes by a well tended lawn. Yet, each home is surrounded by almost identical buildings revealing the inhabitants’ contradictory desire for safety in sameness. The three large format photographs that anchor ISLAND elaborate on this schizophrenic nature of the suburban home. Each photograph features a bungalow set in lush, green environs. But the familiar tranquil is interrupted by monumental, black, spray-painted text that covers the facade of each buildings reading SOS, RUN and HELP respectively. While SOS presents a frontal image of an isolated building, RUN and HELP present us with views of a graffitied house surrounded by its doppelgangers. On closer inspection these eerie crime-scenes are glaringly absent of people, provoking the question: whose cries for help are these and to whom are they calling out? The answer, it turns out, is multi-layered and ambiguous.

Given the fact that the American suburbs took shape in the 1950’s and 60’s largely as a result of “white flight” from inner-city neighborhoods–a history that remains visible in that stark racial segregation that marks rust-belt cities–should we read the words RUN, SOS and HELP in the context of race and class in America? This question is reinforced by the fact that the pictured buildings were foreclosed on during the housing crisis in the mid-2000’s and currently lie vacant in suburban Ohio. The three photographs are not simply images that represent an idea of home, but are in fact documentation of the real homes of people who were unable to continue living in them. Predatory lending by financial institutions in the early 2000’s took advantage of the class aspirations of people eager to own property well beyond their means. After all, isn’t the suburban home the archetypal image of the American Dream, reinforced through cinema and advertising? Considered from this perspective, the words SOS and HELP echo the voices of occupants no longer able to pay hefty mortgages and finally forced to give up their homes. The archival images and ephemera found in these buildings and included in the exhibition, as well as the sculptural fragments excavated from original homes, titled Deconstruction Series, further contribute to the context of the three photographs, placing them within specific sites and personal narratives.

While the archival material grounds these allegorical images of belonging and loss, it does not overwhelm them. The vacillation between allegory and social commentary continues into Frameworks, Strange’s site-specific installation that resembles the skeleton of an A-frame house. The hand-charred, wooden structure makes us consider the fragile nature of home which can so easily be taken away. The black lines that delineate its structure are reminiscent of the wireframes that underlie architectural renderings, but the material presence of burnt wood brings destruction to mind. A home is as much a physical site, defined by spatial configuration as it is an idea: a place cultivated through intimacy, care and belonging. It is an interiority that shelters and protects its occupants from the harsh world beyond its walls. But the containment and privacy that the house provides may itself take on the guise of its opposite–a smothering feeling of confinement and repression. Strange’s insistence that we consider the home simultaneously as a figure of safety and entrapment has a long history. In Freud’s famous 1919 essay, The Uncanny he traces the history of the German word heimleich, which originally connoted safety and security, and over time took on the meaning of seclusion and secrecy, finally making an about turn to mean its exact opposite, unheimlich-frightening and uncanny. Freud draws on this etymology to argue that within every archetype of safety and security lurks its monstrous opposite. From this vantage, Strange’s photographs take on a phenomenological significance that exceeds their sociopolitical context. In his photographs he writes the name of the ghost that haunts the home, right on its face.

While channeled to good effect by surrealists like Man Ray, photography’s special proximity to the uncanny takes us back to the beginning of the medium. In the 1860’s the pervasiveness of “spirit photography” which aimed to capture images of ghosts and seances, pushed a medium that made things visible beyond the edge of its ability. Photography attempted to penetrate the realm of painting, which had long been employed to make the invisible visible. By introducing painting into the photograph Strange joins a lineage of photographers who push against the very limits of the medium. While a painting is understood as being the product of imagination, a photograph always implies an existential relation to reality, a feeling, as Roland Barthes says, of “that has been.” It is in this space of tension between presence and absence, tranquility and a cry for help that Strange’s photographs hold us.

The close relation between suburbia and the uncanny is also a theme explored in film and fiction from David Lynch’s Blue Velvet and Lars Von Trier’s Dogville to the more recent Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn, each probing a disturbing interiority, whitewashed by the socially conscripted facade of cheer and order that the suburbs promise. The medium of photography, which captures the surface of reality, is particularly apt for such an exploration. The photograph already implies the invisible through areas of shadow (the interior of the building in Strange’s photographs) and the world beyond its framing edge. The series of architectural fragments titled Deconstruction Series also point to a whole that remains elusive. Like memories that are often partial and subjective impressions of places and experiences, Strange’s photographs and sculptures put equal emphasis on presence and its shadow, absence.

The complexity of Ian Strange’s ISLAND lies in the balance it strikes between the socio-political realities that dictate who owns a home and who cannot, as well as the psychological experience of memory, longing and loss that we all carry with us through our lives from one home to the next.

—

Sreshta Rit Premnath (b. 1979, Bangalore, India) is a New York-based artist and academic. He is the founder and co-editor of the publication Shifter and is Assistant Professor at Parsons School of Design, New York.

STATEMENT: 'Making Island'

by Ian Strange

Originally published in Art Monthly Magazine, November Issue, 2017

STATEMENT: 'Making Island'

by Ian Strange

Originally published in Art Monthly Magazine, November Issue, 2017

Making Island

by Ian Strange

ISLAND is a body of work I started in the USA in 2015 and presented in my recent solo exhibitions at the Fremantle Arts Centre, Australia and with Standard Practice, New York. The exhibitions are anchored by three new large photographic works documenting interventions directly undertaken on foreclosed homes through Ohio’s ‘rust-belt’ region as well as research and work created in Detroit and New York between 2015 and 2017. The exhibition presents artefacts retrieved from inside the homes; found photographs, research, sound works, the reconstructed sections of now demolished homes, as well as drawings created in development of the work.

ISLAND aims to create a poetic connection between the specificity of each GFC affected home and the larger themes they have come to represent. Looking at the icon of the house as a deeply vulnerable object and personal vessel for memory, identity and aspiration. ISLAND reflects on the home through the metaphor of the desert island; a place of simultaneous refuge and entrapment. Beyond the context of economic foreclosures, the works touch on a wider idea of suburban isolation and angst. The use of text such as ‘SOS’ directly reference historical instances of entrapment and rescue; letters written in the sand of an island, on the roofs of nail houses in China or on homes following Hurricane Katrina. By presenting these large scale works alongside research and intimate artefacts found inside the homes is intended to transgress notions of scale and interplay the monumental with the intimate and intangible.

In its approach and presentation, it is a body of work I have been building to for the past 8 years.

Since 2010 my practice has largely focused on ideas of suburbia. I am specifically interested in the house as psychological symbol and the false sense of permanence it seems to represent.

In this time, I have created large scale sculptures, films, photographic works and site-specific interventions onto suburban homes between the U.S., Australia, New Zealand, Norway, Poland and Japan. It is a body of work that has spanned a wide socio-economic reach, working in neighbourhoods in current conflict & disaster zones, affluent neighbourhoods & foreclosed suburban post-GFC housing.

These works are most often direct markings or cuts made into the homes, in an attempt to place the psychological interior of the houses onto their exteriors. Creating these works also involves collaborating with large teams, technicians and the local communities themselves.

The homes are almost always demolished after the work is executed, so it is the documentation process which gives the work its final form.

I work with teams to cinematically light the works, and they are consciously shot in hours of intense suburban isolation. This not only removes each home’s specificity, but also places each house in the familiar space of mass culture; the home seen in film and television. By borrowing the familiar tropes of commercial film and photography, it allows each work to remain a nod to its original context, while also standing as a broader symbol for all homes. This allows the works to be considered as a universal house; the idealised and imagined home. They are dwellings of projected memories from the viewer; of their childhood, of family, belonging and isolation.

While ‘ISLAND’ falls neatly within these years of work, it is also a departure. It is the first exhibition which presents the specificity of house locations alongside process, found artefacts and research. Working from primary documents and objects has allowed me to carve a collective idea of suburbia while remaining a testament to the individual homes and the narratives of their inhabitants. To present this within an exhibition, is to greater place my role as an artist creating connections between the research, process and larger poetic truths.

ESSAY: 'Domestic Interventions'

by Daniel Palmer

Originally published by RMIT University, and Architecture Australia, July 2018

ESSAY: 'Domestic Interventions'

by Daniel Palmer

Originally published by RMIT University, and Architecture Australia, July 2018

Domestic Interventions

by Daniel Palmer

About a decade ago, as I was renovating my first house – a rundown 1940s clinker brick housing commission house – a small photograph dropped onto the floor. It had slipped out from where it had been resting, behind the back of a timber mantelpiece over a grimy kitchen chimney. This piece of paper – as yellow as the cigarette-stained walls – showed a small group of young people in swimsuits. It offered little in the way of information, say of where or when it was taken, or who was pictured. It was simply an abandoned portrait of a group of people quite possibly now dead, an image marked by what Roland Barthes, in Camera Lucida, famously called the “catastrophe” of time. I admit that what I really wanted the photograph to depict was the house my partner and I had just committed to living in, perhaps as seen in happier times. No such luck. Nevertheless, the photo appeared like a magical trace of the previous owner who had lived in the house all her life and who had, by the accounts of various neighbours, been found dead in the very kitchen I was now occupying.

My immediate response was to photograph the found photo with my digital camera, in situ, perhaps intuiting that this represented an instance of photographic finding that is nearing extinction. No doubt that action, like my overall response, reflected my own reverence for photography. But it was also indicative of a broader interest in found photography among artists and collectors. Of course, artists have worked with anonymous and found photographs ever since the Dadaists and Surrealists recognized photographs as “readymade” fragments, but it seems as if we are only now able to sift through the full mess of the last century’s mass proliferation of images. Our current attraction to the found photograph is clearly symptomatic of a set of anxieties around photography’s digital recoding, even extending to the status of our memory itself. After all, as art historian Mark Godfrey recently mused, “one day soon there will be no more discarded photographs that have been taken, rejected, fingered, scratched, lost, found, and wondered about, no more object/images cluttering our lives.”1 In the meantime, we witness a rapid trade in other people’s “obsolete” slide collections and family albums in junk stores and on eBay, with artists adopting a variety of narrative techniques to explore the always incomplete, partial and amnesiac nature of the photographic archive, along with the melancholic intensity of its absences and the pathos of its unhomely repetitions.

Enter Ian Strange, whose most recent work is comprised of a collection of nostalgic photos of old houses marked and painted with acrylic and ink, which function as both studies and versions of his real-world interventions. Displayed, like the found photograph I began with, on a mantelpiece. I cannot help but assume that the fact that Strange was born and raised in Perth, that most isolated of suburban cities, helps to explain his work. If Perth’s shiny veneer barely conceals a spiritual emptiness, then the searing boredom of its suburbs is typically expressed in materialist hedonism and languid longings. However, it can also find a cultural response in unauthorized, underground creativity. Indeed, Strange began his career in the early 2000s as a graffiti artist under the moniker Kid Zoom, rising to international prominence for his photorealistic use of spray paint before relocating to New York in 2010. He also studied filmmaking, which is obvious from the cinematic scale and nature of his productions.

Living in America, Strange became fascinated by two things: first, ideas of home and suburbia, and second, the impact of the 2008 global financial crisis on the USA housing crisis, then in full swing. The first is personal, the second is public, but both are political. As artist and writer Sreshta Rit Premnath notes in a text accompanying the project,² Strange’s work references the brutal political realities “that dictate who owns a home and who cannot,” and at the same time “the psychological experience of memory, longing and loss that we all carry with us through our lives from one home to the next.” A revealing opening shot in an ABC documentary on Strange’s work called Home: The Art of Ian Strange shows his library with Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space positioned next to Joshua Comaroff and Ong Ker-Shing’s Horror in Architecture. By now we all know that the suburban idea of home – the idealized image of a detached house with its patch of lawn – is a profoundly ambiguous one. And it is precisely this ambiguity that Ian explores in major bodies of work that have included such dramatic and ambitious gestures as recreating a full-scale replica of his childhood home only to graffiti its front wall (Home, 2011); spray-painting houses earmarked for demolition with giant blood red crosses, which, especially when photographed, mimics the process of crossing out unwanted photographic negatives; setting a house on fire to create a spectacular film (Suburban, 2011–13); cutting out sections of weatherboard houses to exhibit them in galleries, and cutting a house open, Gordon Matta Clark-style, to artificially illuminate it from within for a commission in post-earthquake Christchurch (Final Act, 2013); painting red brick Australian houses entirely black in an act of gothic erasure (Shadow, 2015–16); and even crash-landing a scorched three-bedroom house on the forecourt of the Art Gallery of New South Wales (Landed, 2014) – the last two with a nod to white Australia’s alienated condition of colonial habitation. In all of these works, each of which informs the next, Strange reveals the house to be a vulnerable object – physically and psychologically unstable – contrary to conventional ideas of family and stability. And significantly, these “interventions”, as he calls them (which can also be thought of as psychological attacks on the house), are first drawn up as storyboards, then enacted with the help of collaborators (often involving various community leaders) before being documented with film and photography in a lighting style borrowed from the universally poetic language of Hollywood cinema.

Island is Strange’s most recent body of work, “anchored,” as he puts it, by photographs documenting three interventions made directly onto suburban homes in Ohio’s Rust Belt region between 2015 and 2017. One of these photographs was included in a recent exhibition at RMIT Project Space, which is a modified version of a larger exhibition. The homes depicted are post-GFC foreclosed homes. Doomed homes. But these are not simply voyeuristic images of poverty, the latest version of disaster tourism. Strange and his collaborators have gone to extensive effort to repair the houses and gardens before marking and filming them. The houses are like the embalmed body of a loved one at a funeral parlour. Indeed, when the houses are demolished, the building material is pushed into the concrete basement – those famous basements we see in American horror films enable a burial in which the house literally forms its own coffin.

In this new work, Strange has produced a new form of house portrait: houses that speak. For the innovation here is text: three words, writ large across the facades in black spray-paint, all from the emergency lexicon: HELP, RUN, SOS. Words that also evoke the context of race and class in America, if you know your history of American suburbia and its link to the so-called “white flight” from inner-city neighbourhoods. The words also evoke the title of the work, Island, suggesting a place of refuge but also of possible entrapment. This metaphorical is inspired by a hauntingly beautiful found photograph of a house in a flooded forest that graces the cover of the book Island, published to accompany the new work. Published by PAMPAM Press (the book is designed by Jack Pam, son of photographer Max Pam) the limited-edition book, with a stiff concertina card, is something of an architectural monument in itself. It also includes artefacts collected at “the intervention sites” that speak of the lives lived inside the houses, as well as research material and “reference images” that speak to broader forces of history – from eviction notices to Hurricane Katrina.

--

1. Mark Godfrey, ‘Photography Found and Lost: On Tacita Dean’s Floh’, October, 114, 2005: 119.

2. Sreshta Rit Premnath, ‘Ian Strange: Island’, www.ianstrange.com/works/island-2015-17/text-i, November 2017.

--

Dr Daniel Palmer is Associate Professor in the Art History and Theory Program and Associate Dean of Graduate Research in the Faculty of Art, Design & Architecture at Monash University. Palmer's research and professional practice focuses on photography, contemporary art and digital media. His book publications include Photography and Collaboration: From Conceptual Art to Crowdsourcing (Bloomsbury 2017); Digital Light (Open Humanities Press 2015), edited with Sean Cubitt and Nathaniel Tkacz; The Culture of Photography in Public Space (Intellect 2015), edited with Anne Marsh and Melissa Miles; Twelve Australian Photo Artists (Piper Press, 2009), co-authored with Blair French; and Photogenic (Centre for Contemporary Photography, 2005).