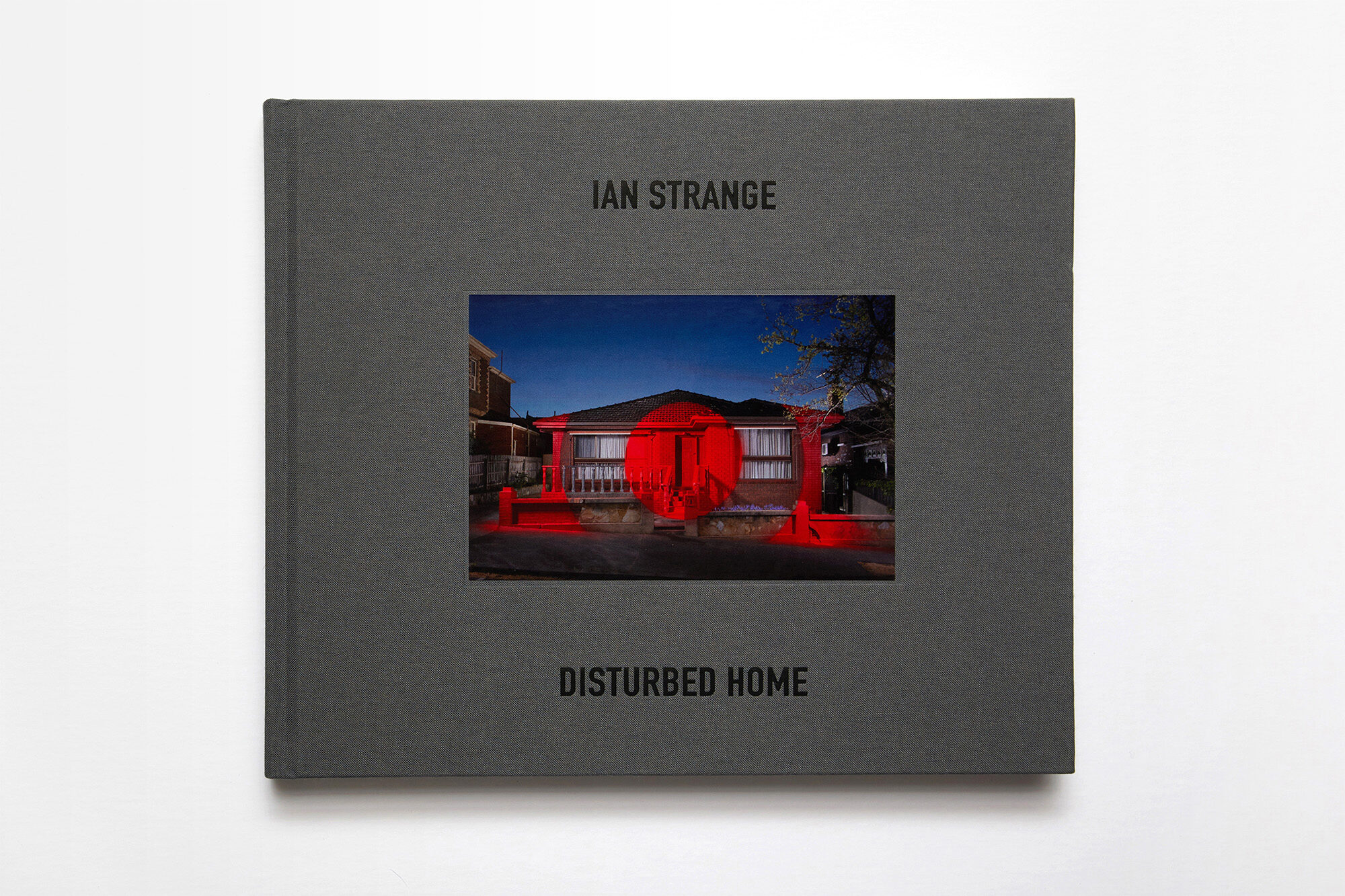

Disturbed Home, 2022

Disturbed Home, 2022

Monograph

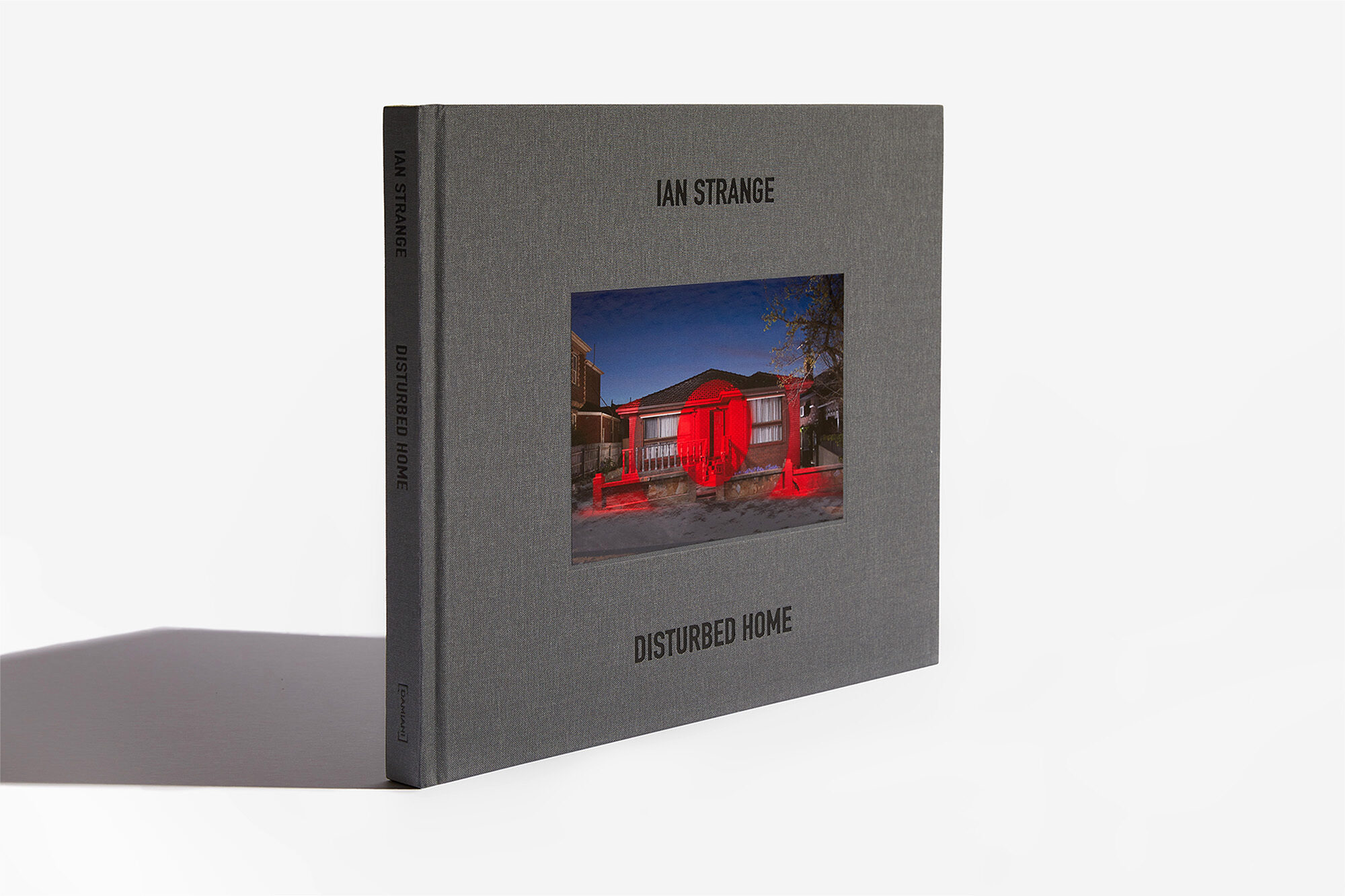

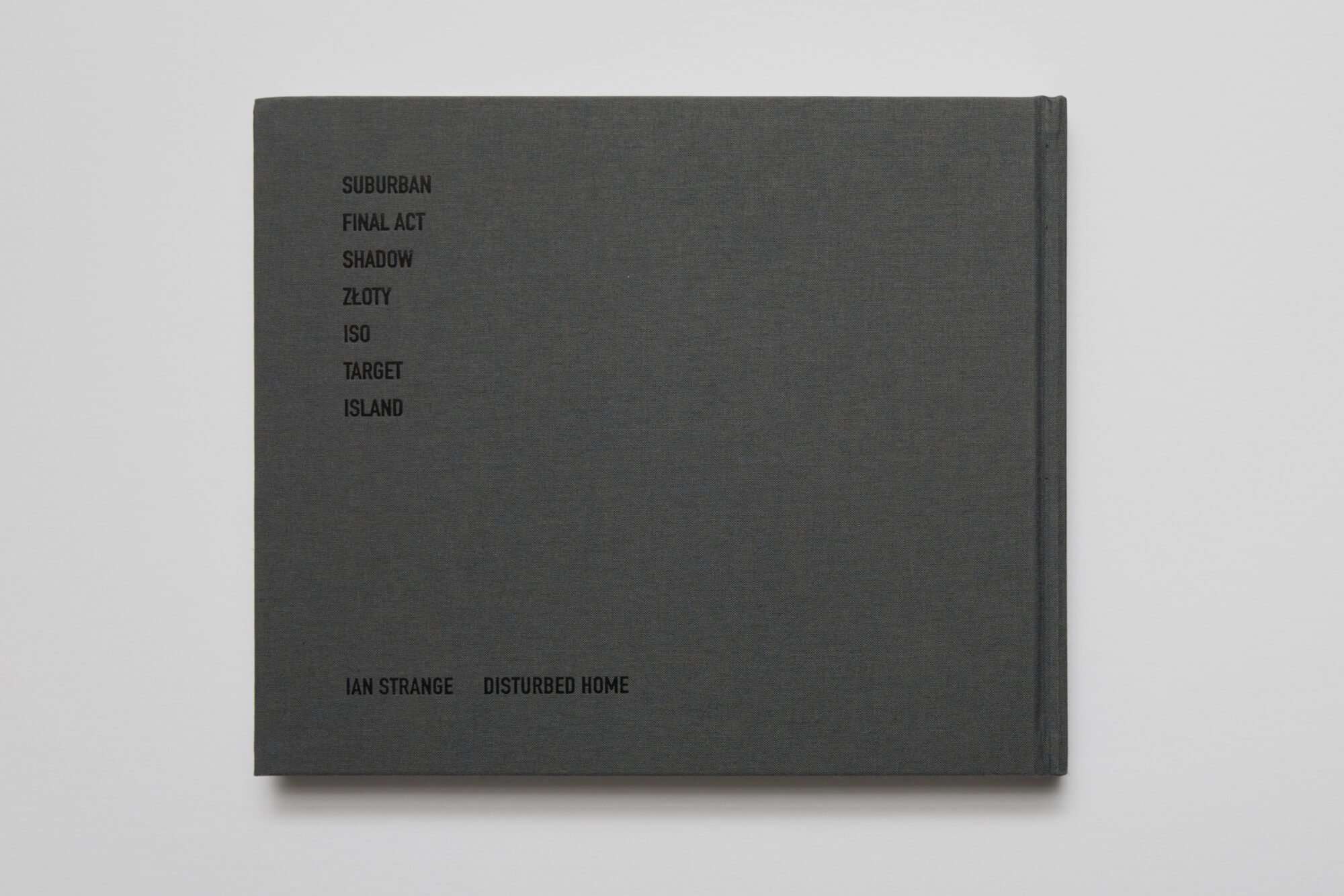

Ian Strange Disturbed Home is the first comprehensive survey of Ian Strange's architectural interventions, including photographic and filmic interpretations of those works. Highlighting projects from the past 12 years and spanning geographies from Strange's native Australia to New Zealand, Japan, Poland, and the US, Strange's provocative transformations of damaged or abandoned homes unlock themes of social upheaval and geographic displacement caused by economic blight, environmental disaster, and migration.

Published on the occasion of the 2022 FotoFocus Biennial, Disturbed Home features lucid commentary and original documentation of numerous distinct projects. Also included are scholarly essays by FotoFocus artistic director and curator Kevin Moore and Britt Salvesen, curator and head of the Wallis Annenberg Photography Department and the Prints and Drawings Department at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). Essays address Strange's practice within traditions of photography, film, public sculpture, architectural and environmental studies, and installation.

PUBLISHER DAMIANI

DESIGN Bec Stawell Wilson

BOOK FORMAT Hardcover, 11 x 11 in. / 156 pgs / color.

PUBLISHING STATUS Pub Date UK 3/31/2022 | Pub Date USA 5/24/2022

DISTRIBUTION D.A.P. (USA) Thames and Hudson (UK/EU/AU)

Published with the support of DLGSC and FotoFocus.

ISBN 9788862087339

Writing

ESSAY: 'Suburbia as Mystery and Image'

by Britt Salvesen

Originally published in Disturbed Home (Damiani Editore, 2022)

ESSAY: 'Suburbia as Mystery and Image'

by Britt Salvesen

Originally published in Disturbed Home (Damiani Editore, 2022)

Suburbia as Mystery and Image

by Britt Salvesen

[PDF]

Clichés about suburbs tend to emphasize their uniformity, anonymity, and monotony. Photographs of suburbs may reinforce these attributes, taking on a kind of emulative consistency. Depending on context and intention, an apparently ordinary image of a single-family home could be a real-estate advertisement, family snapshot, or work of art. That same image could be perceived as optimistic or pessimistic, comforting or alienating, nostalgic or neutral, descriptive or abstract. Clearly these bland, homogeneous places provoke a range of strong emotions. Ian Strange represents the most recent generation to undertake renovation of the subject’s photographic iconography. The feelings we have about home, value, identity, class, and ownership have become only more complex and ambivalent in an era of global postindustrial capitalism, with its attendant financial crises, increasing wealth gaps, and rising numbers of people without housing. Since beginning his exploration of the subject with personal memories of his childhood home in Western Australia, Strange has launched a series of ambitious projects that encompass a sociopolitical awareness of homes as psychological icons and physical assets

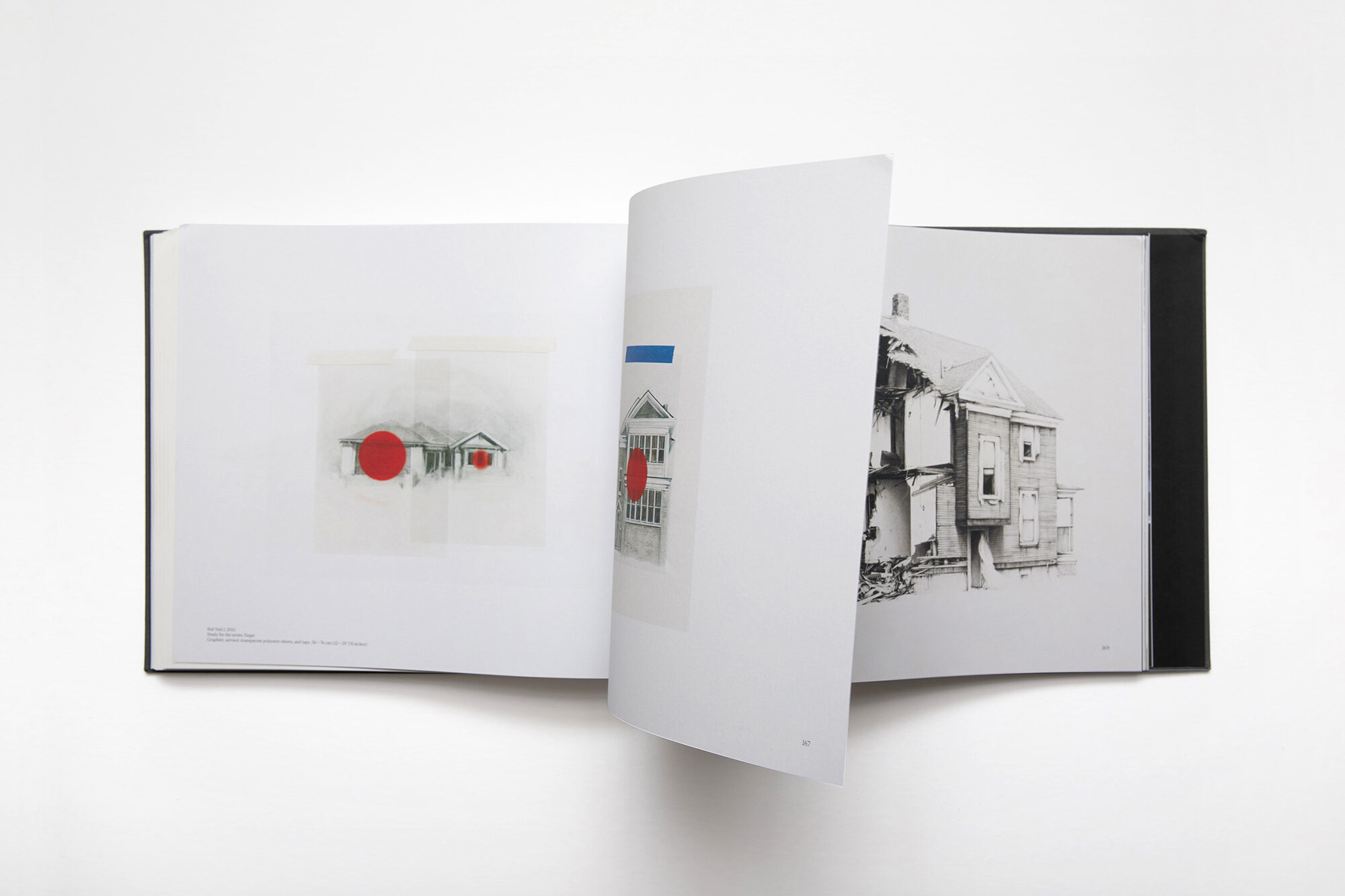

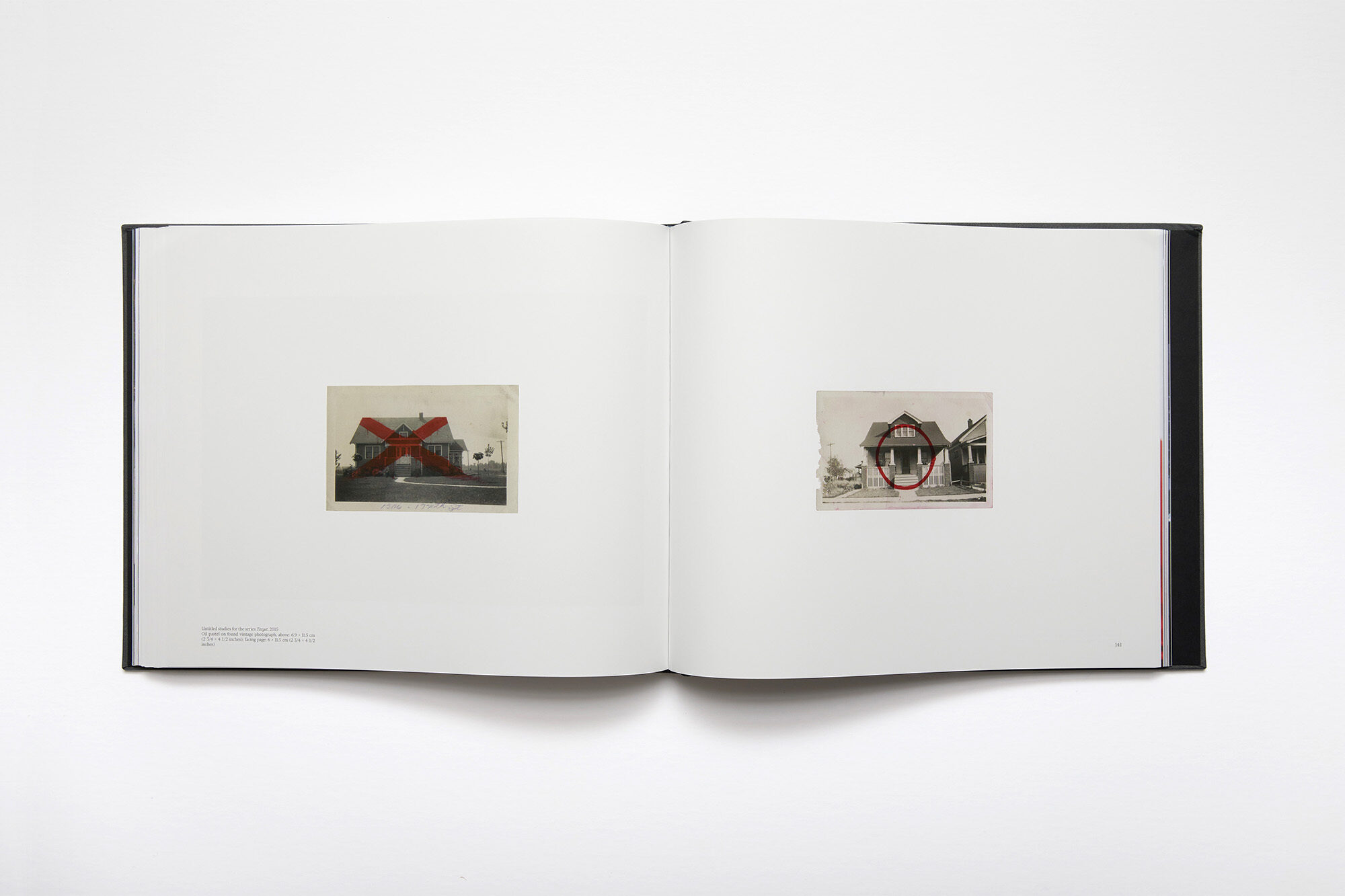

Strange alludes to the archive of suburban imagery produced in many media over many years while adopting a point of view and process entirely his own. An open, consultative phase typically initiates a progression toward formal rigor and carefully calibrated presentation. Cumulatively, Strange’s work examines not only architecture and suburbanism as such, but also the impermanence and mystery central to human experience, which always escapes the containers we build for it. As seen in his altered found snapshots (see pages 140-45), the artist’s hand animates and threatens the structures, questioning their stability and permanence while perhaps revealing latent energies. Such works function as both sketches and statements, testifying to Strange’s procedural impulses to mark surfaces, interrogate photography, and “break down walls” in various material and conceptual ways.[1]

Photography was instrumental in stimulating the post–World War II boom of new housing developments for middle-class white families in Australia and North America. Whereas sweeping aerial perspectives rendered suburban houses toylike in endless rows, ground-level views in design magazines and real-estate advertisements isolated them in verdant lawns. By the early 1970s, the National Association of Realtors was America’s largest trade association, with over four hundred thousand members and specialist councils for industrial, office, residential, and other areas of brokerage. Yet amid this professionalization and standardization, home remained a deeply personal idea, demanding significant emotional as well as physical labor to maintain.

Some who were raised in these postwar communities longed to escape them when they came of age in the ’70s, willingly trading suburban comforts and beauties for the challenges of purportedly blighted cities or desolate highways. How could aspiring photographers deal with the environmental, economic, and political crises that pervaded society in a decade characterized by “disillusion and cynicism, helplessness and apprehension,” according to Americans polled at the time?[2] While some continued to seek unblemished natural wonders, perpetuating the immersive, romantic, large-format ethos of Ansel Adams, a younger cohort of artists took up photography in order to take a critical perspective on the environment as they saw it: human-made and human-altered.

For some artists, irony was the flavor of choice. Dan Graham created a twist on the classic Life photo essay with the layout of Homes for America, 1965; Ed Ruscha defied the precious associations of the artist’s book with small, laconic volumes such as Some Los Angeles Apartments, 1965, and Real Estate Opportunities, 1970. For Graham and Ruscha, photography was simply a means to an end, essentially illustrative. To varying degrees, the ineptitude or banality of their imagery contributed to the work’s meaning, as did the fact of photography’s reproducibility, which in turn suggested and sustained an exploration of seriality. This purposeful deskilling in art—a rejection of artisanal proficiency and manual virtuosity—ran parallel with the gradual triumph of the mass-produced object or image over the unique, handcrafted one and mimicked the lowering of skill levels across American capitalism generally and in housing specifically.

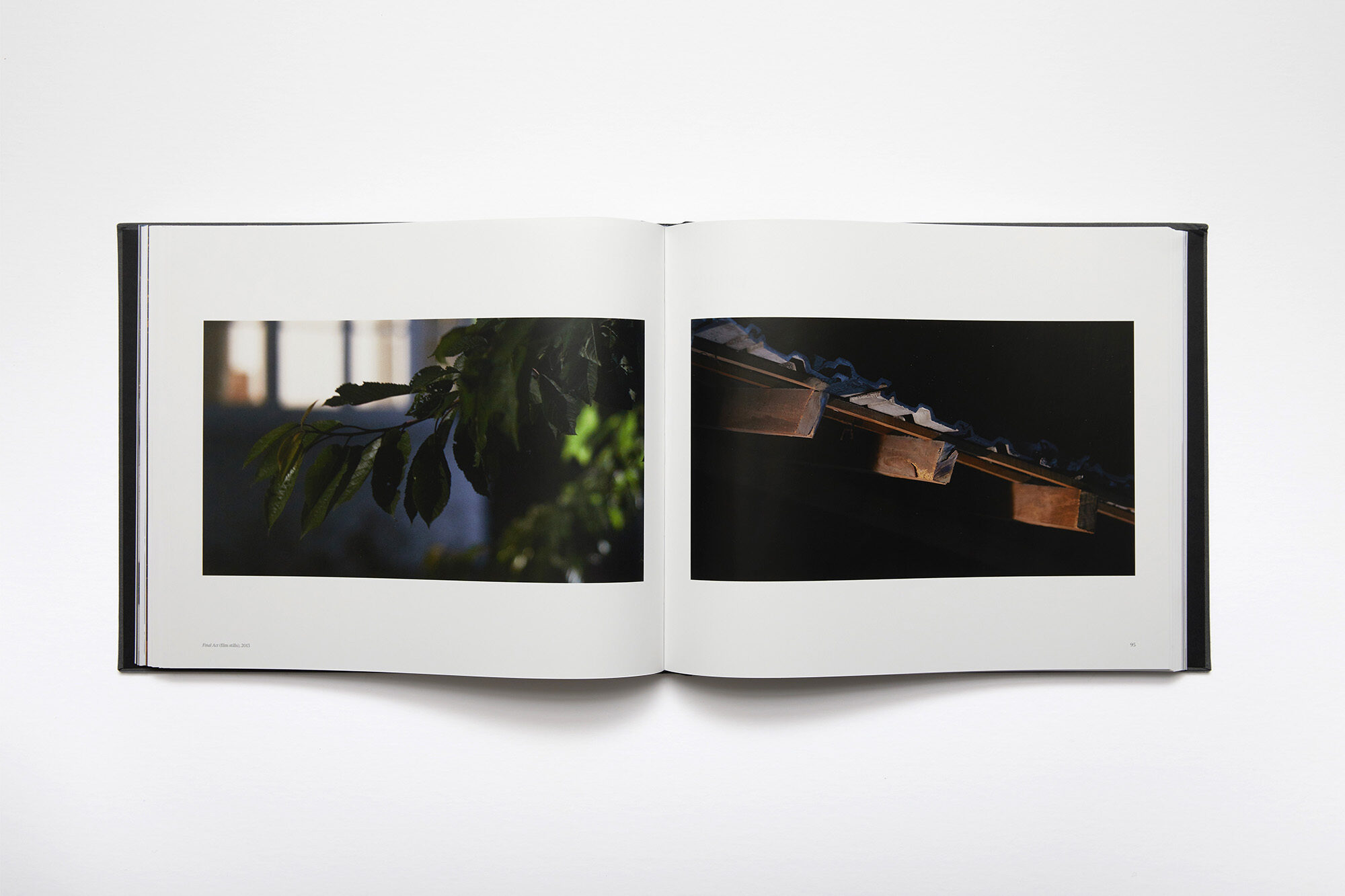

The house as subject and object of conceptual art was most fully realized in a series Gordon Matta-Clark made from 1972 to 1978, known as his “building cuts,” which endure in the form of photographic and filmic documentation. One of the best known is a frame house in Englewood, New Jersey, that Matta-Clark sliced vertically down the center; he then jacked up the cinder-block foundation to open a narrow V shape, exposing the structure’s interior to the elements, negating its function, and dooming it to demolition within three months (see page 38). In 2013, when Strange was invited to create works in the residential “red zone” in Christchurch, New Zealand, badly damaged by earthquakes in 2010–11, he encountered houses resembling latter-day Matta-Clarks. However, the destruction did not represent a controlled artistic gesture but a largescale disaster that displaced thousands of citizens. Strange approached the commission carefully, aware that the community was struggling with loss, relocation, and related stressors. Preserving images of houses slated for demolition, the project Final Act had a documentary function, but more significantly it fostered community dialogue. Final Act required six months of planning and preparatory meetings, culminating in three weeks of on-site collaborative work, during which Strange—aided by volunteers, engineering specialists, and photography and film crews—transformed four houses by making geometric cuts through the walls, painting the interiors white, and illuminating the resulting structure from within. The subsequent installation of photographs, film, and sculptural “extracts” from the houses allowed for a symbolic reentry into the destroyed structures.

The empathetic power of Strange’s Final Act derives in part from the care with which he crafted the individual works; there is nothing offhand or improvisational about their presentation at Christchurch’s Canterbury Museum. This precision has antecedents in the photographic approach associated with New Topographics, named after a landmark 1975 exhibition at the George Eastman Museum in Rochester, New York. Responding to Ruscha’s and Graham’s apparent rejection of photographic competence, the New Topographics artists addressed the same subject matter—the built environment, primarily residential—with a quality-control mindset. Maintaining that neutrality was an intentional artistic position, they did not adopt unconventional viewpoints or make expressive gestures but nonetheless developed individual styles. For example, Lewis Baltz in his Tract Houses, 1972, and Prototypes, 1967–71, set his 35mm camera on a tripod in order to create rigorously geometric compositions, choosing high-contrast film intended for copy-stand use to emphasize the houses’ graphic linearity. Baltz intended his photographs to be minimalist objects; the prints, as he explained, “had to be well made—to give [the work] authority, it had to be high-definition, it couldn’t have shake or blur.”[3] Judy Fiskin also distinguished her work through its objecthood. Several of Fiskin’s early photographic series, including Stucco, 1973–76, survey the residential architecture of Southern California. At first glance her images appear to be contact prints, but in fact Fiskin used 35mm film and an enlarger to establish what became a signature format for her: a small size that draws the spectator in close and replicates the experience of looking through the camera’s viewfinder.[4]

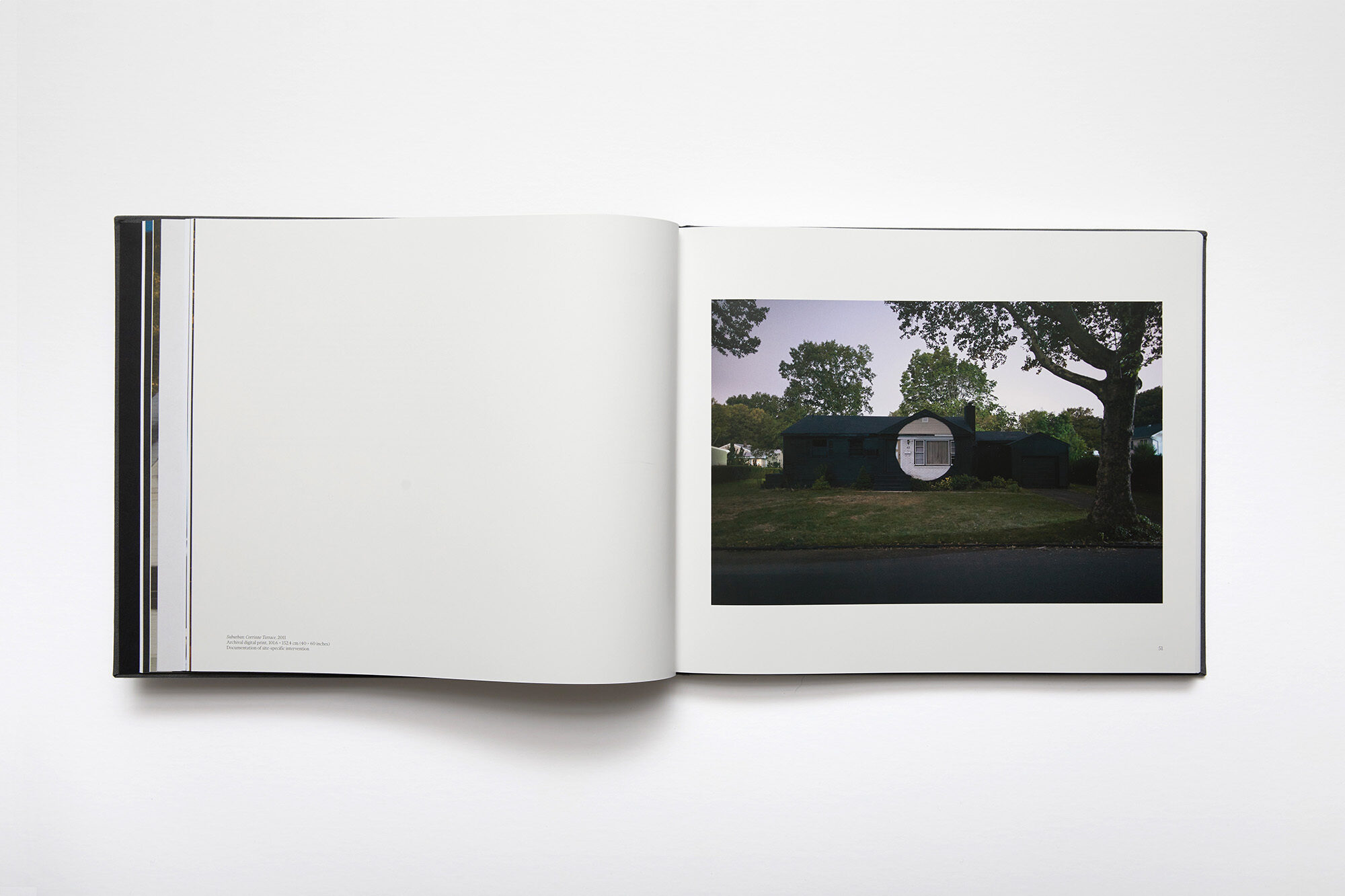

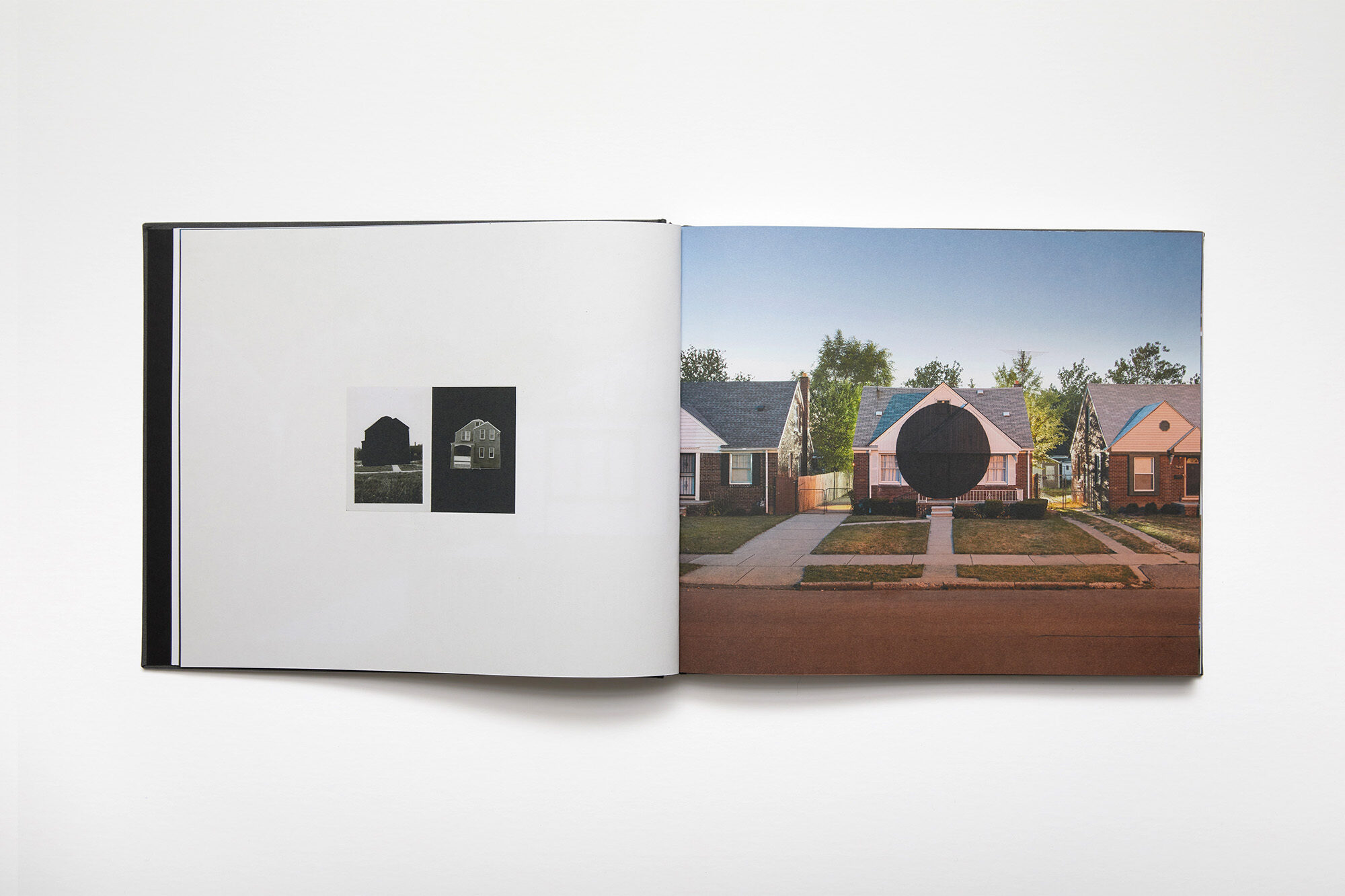

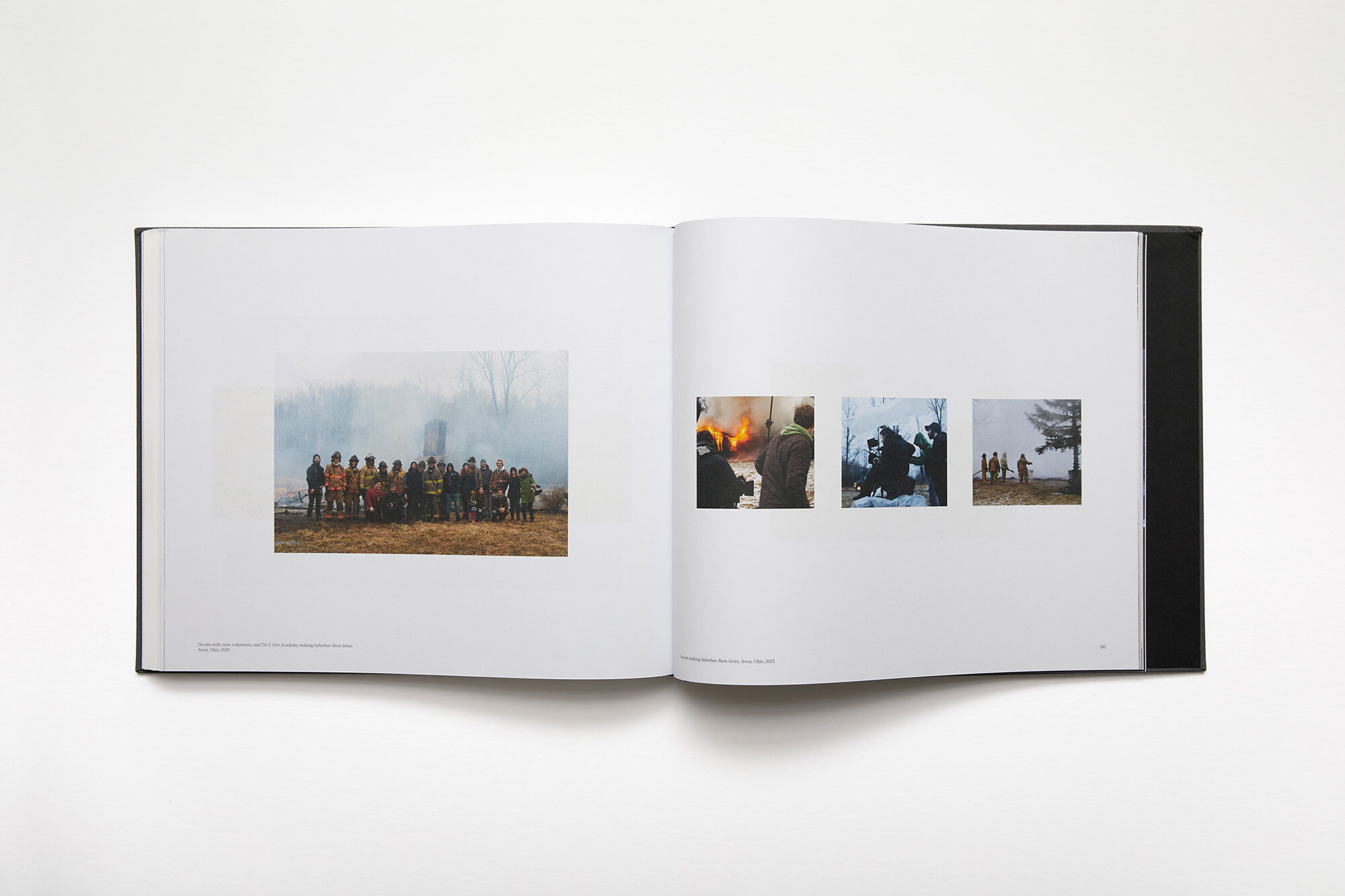

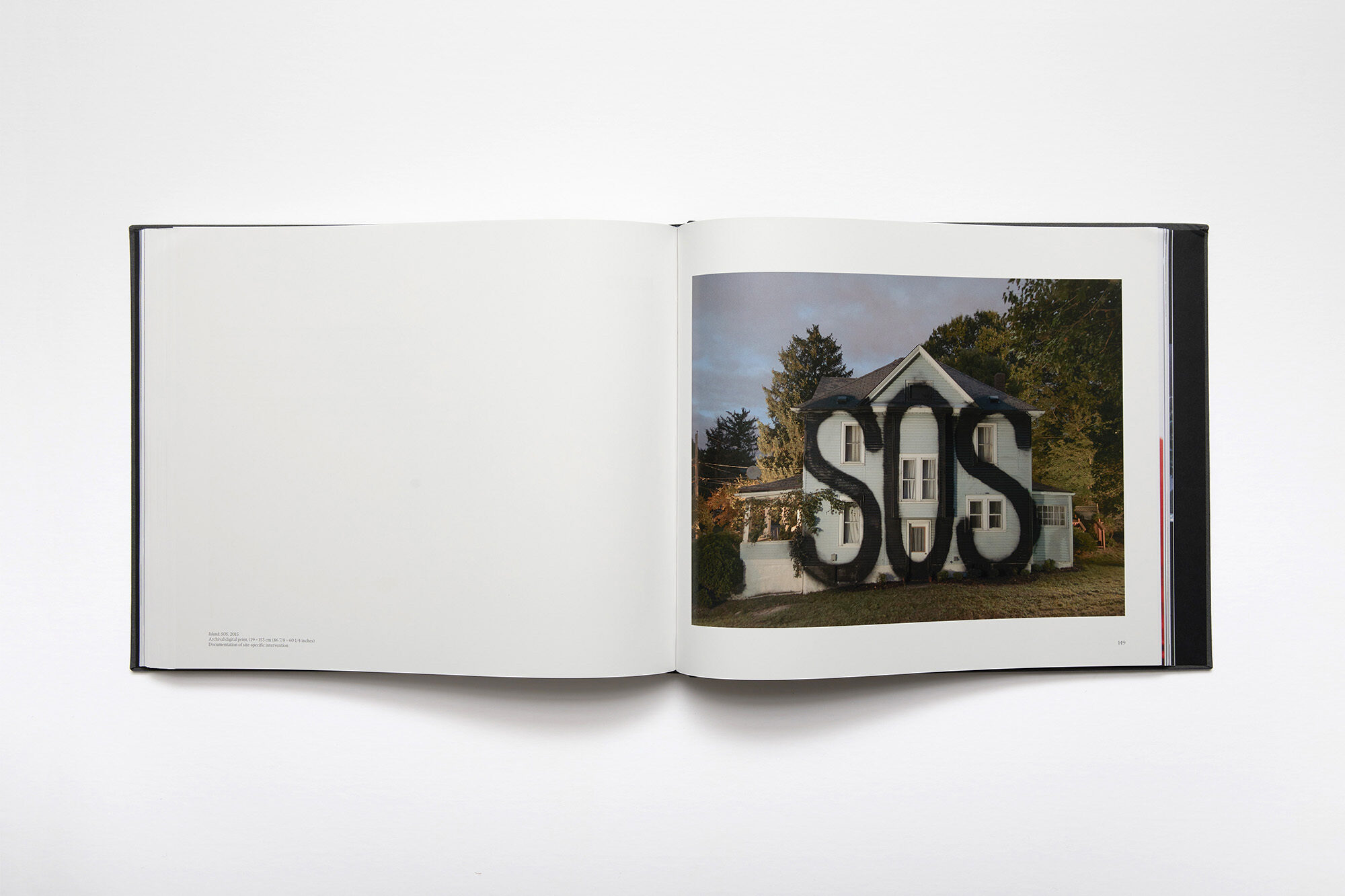

Working with the technologies of the twenty-first century, Strange in his 2013 installation Suburban deployed scale, color, juxtaposition, and moving images to convey his ambivalent relationship to the titular subject (see page 49).[5] Like his ’70s predecessors, he could safely assume that viewers had experience with, even 39some sort of investment in, the type of structures depicted. He too is not interested in activating nostalgia but instead asks viewers to reflect on the impact of suburbia on their own identities and values. By painting symbols like large black dots on the exteriors of single-family houses in several American cities—available to him via arts programs or abandonment—Strange makes explicit the fact that we already occupy a position toward these structures, whether previously articulated or not. Still more provocatively, in other examples he superimposed a red X. Seemingly inevitably, the series culminated in the burning of two houses, their destruction recorded in photography and film.

Strange notes the way his work emerges in the “aftermath of crisis, as part of the recovery.” [6] This engagement with larger forces, both in his approach to specific sites and as an observer of global conditions, motivates his formal explorations and critical interventions. As a “digital native,” Strange acknowledges the processes through which images, seamlessly and continuously circulated, can be drained of specificity. In a way, the ideal of the suburban house has similar pretensions to universality, as Strange critiques through his different iterations of key themes: for example, the evolution of Home, from its initial construction on Cockatoo Island in 2011 (see page 27). To its anchoring role in a multi-channel film installation of 2013. In this way, the core idea remains under investigation, vital and relevant to changing contexts.

While Strange pays attention to the sociohistorical differences between American suburbia and its Australian counterpart, he can also exploit the fact that Hollywood’s exports have shaped attitudes around the world. The decade of the 1990s, when Strange was growing up in Western Australia, generated a deep catalogue of suburban utopias and dystopias. To name just a few: Edward Scissorhands (Tim Burton, 1990), The Ice Storm (Ang Lee, 1997), Pleasantville (Gary Ross, 1998), Happiness (Todd Solondz, 1998), American Beauty (Sam Mendes, 1999). The Castle (Rob Sitch, 1997)—“perhaps the most cherished Aussie movie of all time”—follows a rough-around-the-edges suburban father who takes on faceless developers to protect the family home.[7] Meanwhile, HGTV (launched in 1994) generated a nearly undifferentiated 24/7 “theater of the house,” motivating the middle-aged Boomer generation to reinvest in the newer, larger suburbs that David Brooks calls “Sprinkler Cities” in his 2002 screed “Patio Man and the Sprawl People.”[8]

Photography helped refine this theatrical suburban iconography, mobilizing beauty and spectacle through lighting, color, production values, and scale in ways that distinguish this work from that of the New Topographics generation. Perhaps most notably, Gregory Crewdson’s narrative tableaux, unabashedly staged and cinematic, portrayed suburban houses as containers for human emotions, frustrations, and desires (see facing page). Crewdson explicitly describes himself as a storyteller, one who recounts a single tale over and over again.[9] While Crewdson focuses on the northeastern regions of the United States, in 1997 Beth Yarnelle Edwards began a series of staged photographs in the suburbs of Silicon Valley, newly affluent as technology firms and dot-coms came to dominate the global economy. Both Crewdson and Edwards based their projects in areas where they lived, and both included human figures to hint at complicated stories. More akin in scale and affect to feature films than to the deadpan black-and-white prints of the ’70s, this psychologically potent work struck a chord through its mixture of aspiration and ambivalence, in keeping with a dawning realization that the prosperity and hubris of the ’80s had failed to compensate for losses resulting from wars, substance abuse, the AIDS crisis, and other assaults.

The introduction of cinematic aesthetics into photography by Crewdson and others has encouraged many artists, Strange included, to work across both media. Film has been a component in all his major projects, not merely as documentation but as independent artworks. Shadow, 2015–16 (see page 97), is one such multipart work, in which Strange uses color and lighting strategically to convey messages about memory and association. Specifically, he addresses the postwar red-brick suburban house, a humble icon of Western Australia, by covering five such houses entirely with matte black paint, essentially transforming them into black holes. In still photographs, the juxtaposition of the black houses with blue skies, green lawns, and neighboring houses vibrates both comedically and ominously. The film emphasizes the latter mood, eliminating the contrast between monochrome and color to dwell on absorptive blackness, panning slowly across one of the buildings without ever fully revealing the context. “The house appears in an elevated film space, so they feel hyperreal or unreal,” Strange explains.[10] As in his other projects, the tone is achieved through formal means; no people are depicted, yet the environment feels intensely human, perhaps bearing traces of the community collaboration required to realize it.

While Strange’s work demonstrates his awareness of precedents as varied as Ruscha, Matta-Clark, Baltz, and Crewdson, it stands on its own as a twenty-first-century practice and a personal statement about concepts of home, history, memory, and vulnerability. Strange’s expanded understanding of photography includes collaboration, intervention, documentation, ephemerality, and cross-media practice (drawing/ performance/photography/film). He also ponders photography’s implications for surveillance, falsification, and manipulation, as well as its instrumentalization in and beyond the art world. Examining the subject of suburbia from many angles, Strange finds conceptual depths below an unpromising surface.

–

Britt Salvesen is curator and head of the Wallis Annenberg Photography Department and the Prints and Drawings Department at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). Previously, she was director and chief curator at the Center for Creative Photography (CCP), University of Arizona. Prior to joining CCP, Salvesen was associate curator of prints, drawings, and photographs at the Milwaukee Art Museum and associate editor of scholarly publications at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Notes:

1. Chris Johnston, “Rising Up in the Red Zones of Christchurch,” The Age, December 20, 2013.

2. Stephanie A. Slocum-Schaffer, America in the Seventies (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2003), 213.

3. Lewis Baltz, interview with the author, November 14, 2006.

4. “Judy Fiskin Interviewed by John Divola,” in Judy Fiskin, ed. William Bartman (Los Angeles: A.R.T. Press, 1988), Judy Fiskin website, https://judyfiskin.com/press/d....

5. The works in the installation, displayed at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, were executed from 2011 to 2013.

6. Simon Robinson and Steve Mintern, “Artist Ian Strange on Concepts of Home,” in The Politics of Public Space, vol. 2, ed. OFFICE and Tom Muratore (Melbourne, Australia: OFFICE, 2020), 180.

7. Paul Merrill, “The Best Australian Movies of the 1990s,” NME, July 9, 2020

8. Dante A. Ciampaglia, “An Inside Look at How HGTV Became an Industry Juggernaut,” Architectural Digest, July 29, 2019, https://www.architecturaldiges...; David Brooks, “Patio Man and the Sprawl People,” Washington Examiner, August 12, 2002, https://www.washingtonexaminer....

9. Sylvie McNamara, “Submerged and Interior: An Interview with Gregory Crewdson,” Paris Review, October 24, 2016, https://www.theparisreview.org....

10. Ian Strange, in Robinson and Mintern, “Artist Ian Strange on Concepts of Home,” 174.