DALISON, 2021 - 22

Site-responsive architectural intervention, sound and light installation, film work, photographic works, and live performance

DALISON is an architectural intervention and durational sound and light installation, created by Ian Strange in collaboration with musician Trevor Powers, resulting in four new photographic works, an 18-minute single-channel film work, and a one-off community performance.

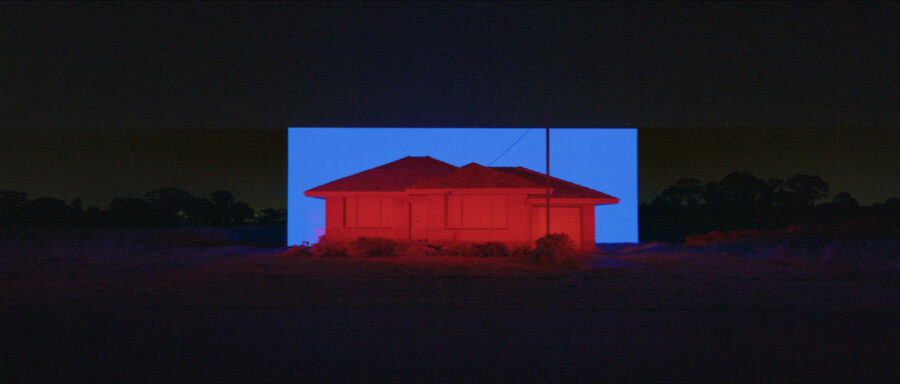

The site-specific work was built around an isolated “hold out” home awaiting demolition at 20 Dalison Avenue, Wattleup, Western Australia. The home was one of two remaining in the former suburb, where more than 300 others had been razed for a controversial redevelopment. Created with permission from the home’s former owners, the installation comprised a large-scale LED video screen, programmed lighting and Powers’ original 18-minute composition, transforming the home into a “performance” of slow, poetic light and sound movements.

The result was a form of “anti-concert”, transmitted out into the void of this now empty suburb. Over three nights, Strange documented this performance in film and photography. On the last night, a small group of the home’s former owners, ex-residents and collaborators were invited to an intimate one-off live viewing of the installation before it was dismantled. This documentation became the foundation for exhibitions and screening events throughout 2022, including at the FotoFocus Biennial in Cincinnati, USA, and the UCCA Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing, China.

A dedicated project micro-site can be found at dalisonproject.com

Photographic Works

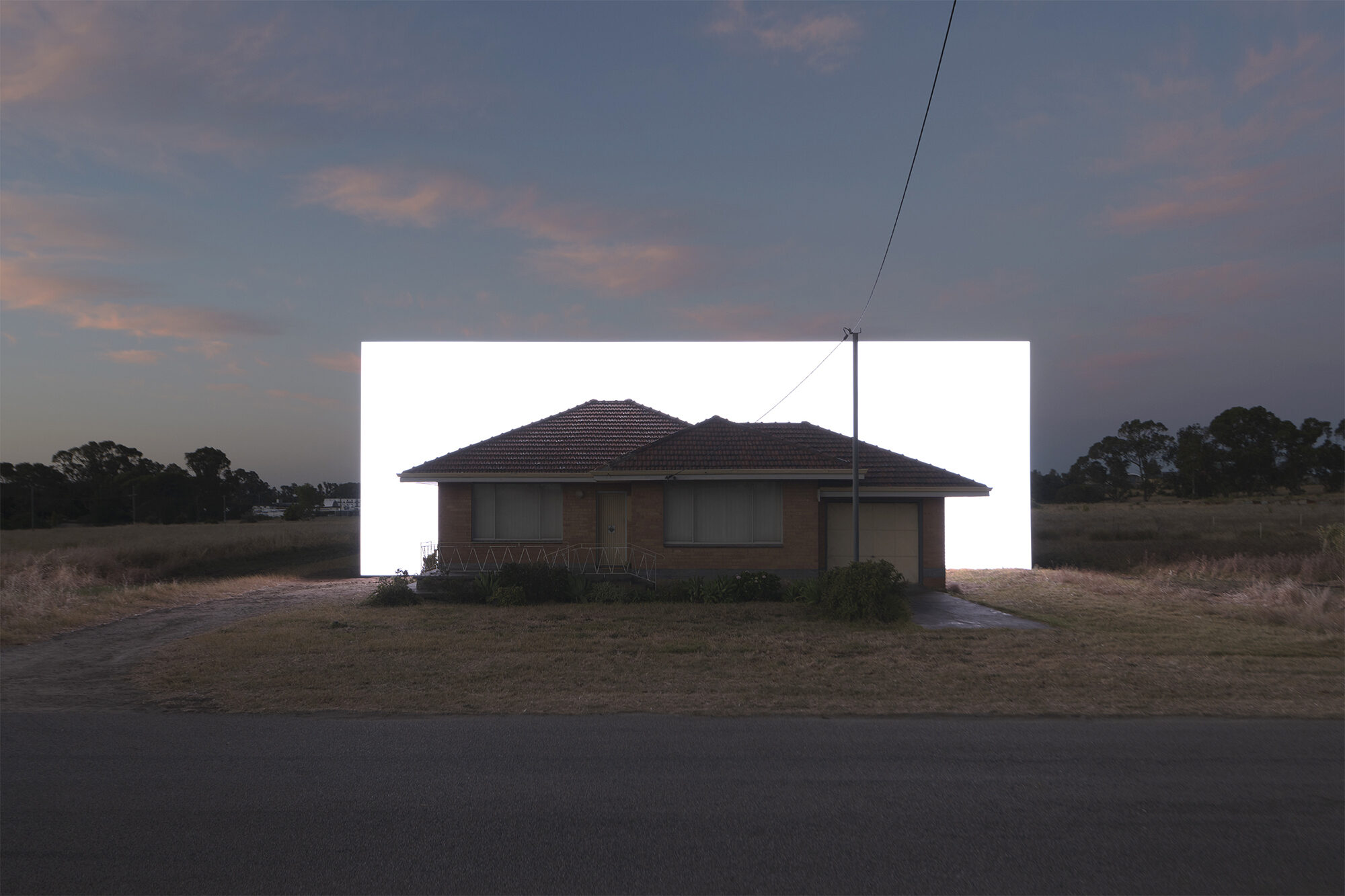

Dalison 1, 2022

Archival digital print

Documentation of site-specific intervention

Perth, Western Australia

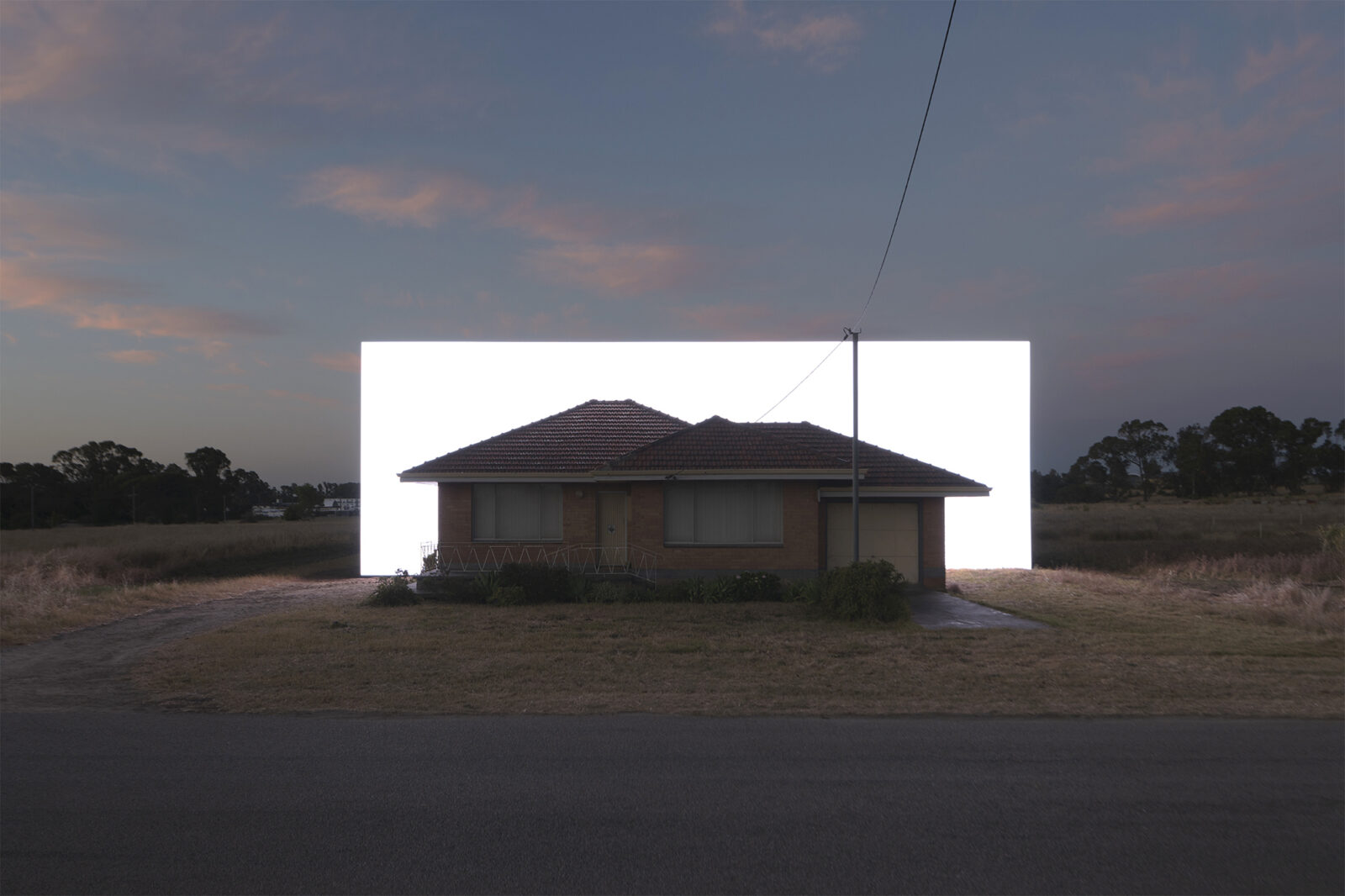

Dalison 2, 2022

Archival digital print

Documentation of site-specific intervention

Perth, Western Australia

Dalison 3, 2022

Archival digital print

Documentation of site-specific intervention

Perth, Western Australia

Dalison 4, 2022

Archival digital print

Documentation of site-specific intervention

Perth, Western Australia

Film Work

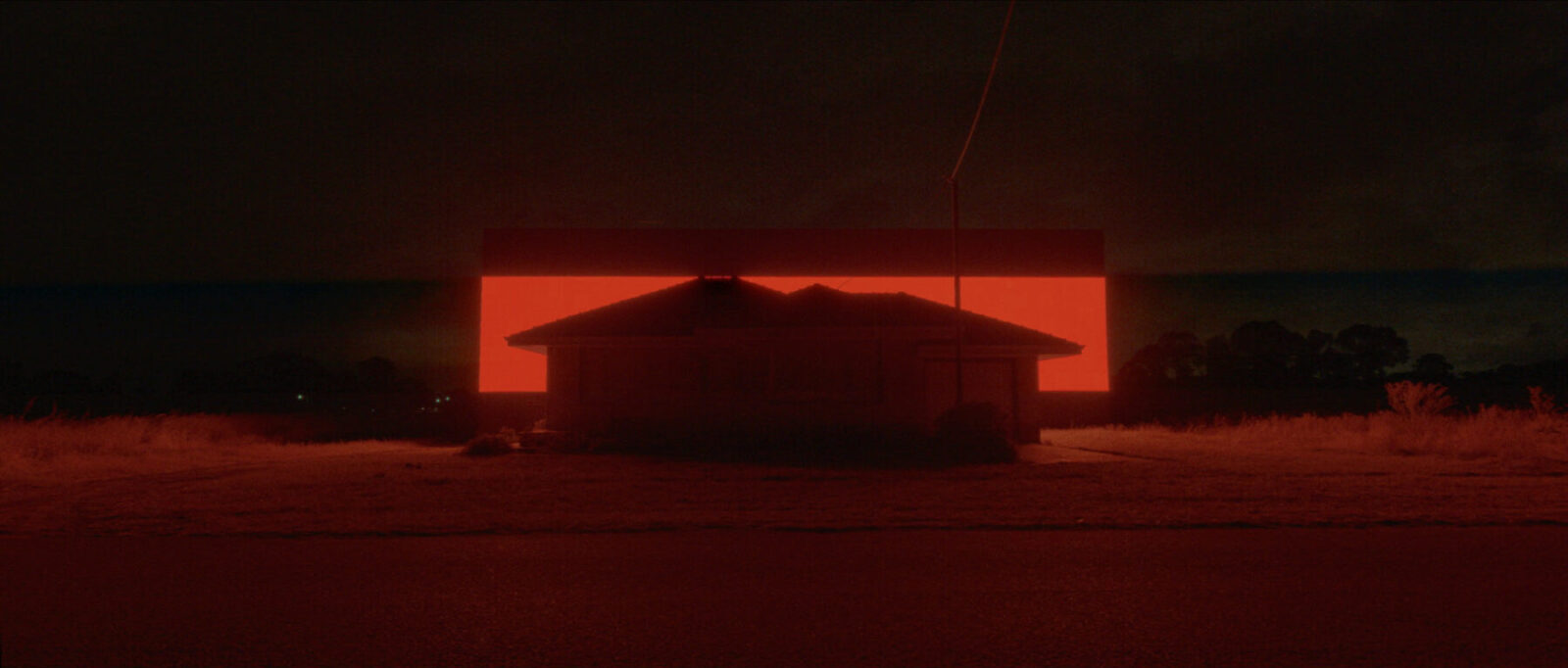

Still frames from film work 'DALISON', 2022

Ian Strange and Trevor Powers

Single-channel film work,

2.40:1, Stereo Sound. 18m05s duration

Still frames from film work 'DALISON', 2022

Ian Strange and Trevor Powers

Single-channel film work,

2.40:1, Stereo Sound. 18m05s duration

Exhibition

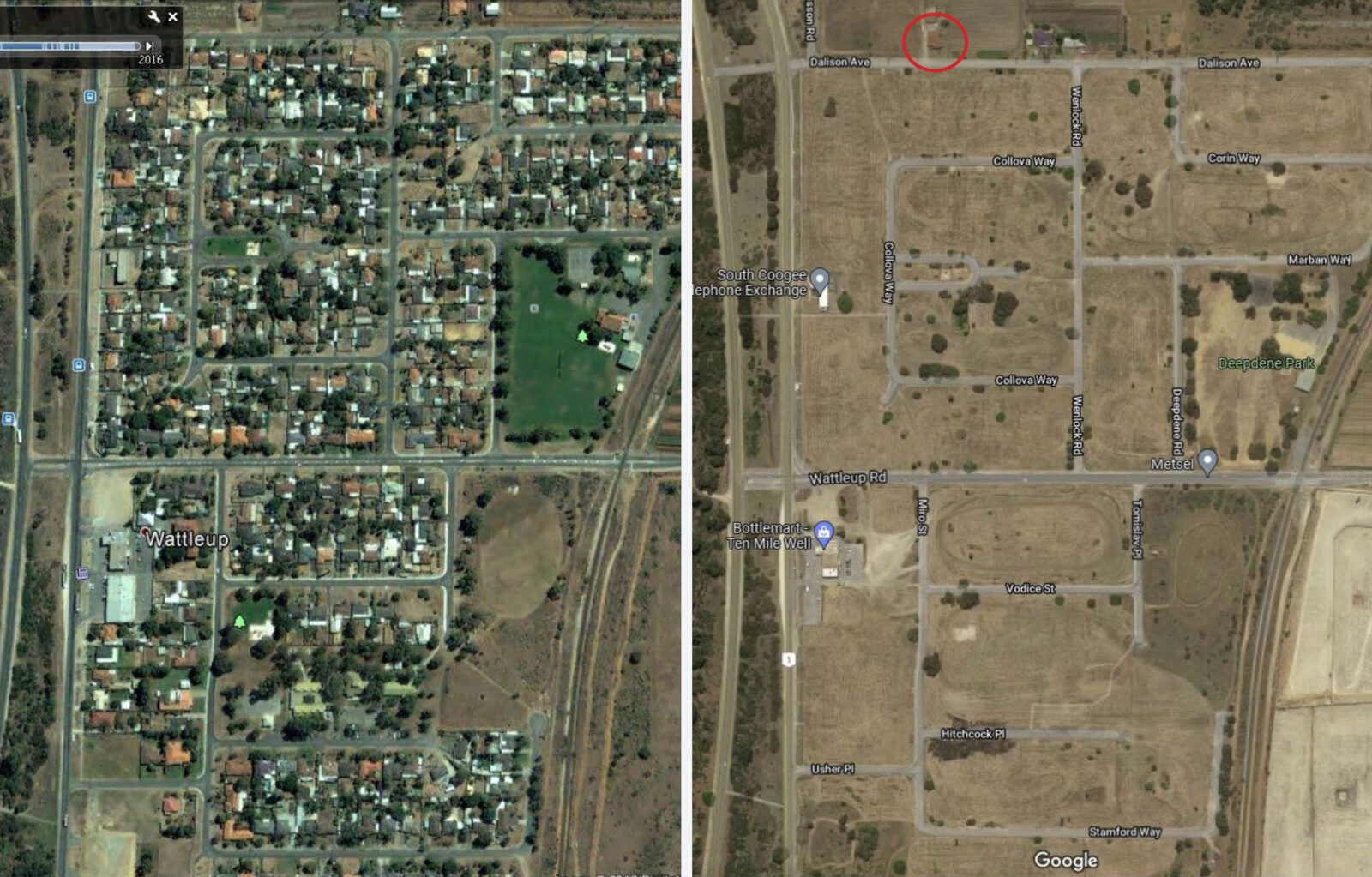

Research + Process

Writing

ESSAY: 'Dalison'

by Eva Hagberg

Originally published February, 2022

ESSAY: 'Dalison'

by Eva Hagberg

Originally published February, 2022

Dalison

by Eva Hagberg

A year and a half ago, we bought a house. Well, we call it a house, because there’s something more solid, more permanent, about calling it a house—but really, of course, this being Brooklyn, it’s a condo. A week after we took possession, we dismantled the entire interior, took the walls down, ripped the floorboards up. We brought a friend over, walked in with only our flashlights to light the way. I saw piles of wood, nails everywhere, a darkened room, illuminated in spots with our iPhones. “This is ours,” I said. “No one can ever take this away.”

As Ian Strange’s work reminds us, that’s just not true.

Homes get taken away all the time, and because of multiple scales of event. Sometimes homes get taken away because of individual losses—foreclosures, job shifts, unforeseen tragedies—and sometimes they get taken away because of “opportunity” or “redevelopment.” And yet, despite knowing this, despite understanding that we have seen peoples’ homes get taken away, we still subscribe, so many of us, to the shared cultural fictions, constantly reiterated and replicated, around the solidity of a home, the absolute unshakable foundation (pun not intended) given a life by the prospect and reality of ownership. There must be a reason it’s called “home ownership,” not “house ownership.”

A project like artist Ian Strange and musician Trevor Powers’ Dalison—centered around a single house in a neighborhood in the town of Wattleup, Australia that once thrived and was home to more than 300 houses but that is now slated, tabula rasa, for new development (called redevelopment)—is at once a deeply emotive reminder of how fleeting what we think of as permanent actually can be, and a devastating testament to how hard we want to hold on. The project—which spans still photography, a site-specific installation done in collaboration with Powers, and a film—is at once a celebration of the house’s inhabitants, who refused to sell when everyone around them did, and a requiem for a place now lost.

Strange’s formal moves, most evident in the still photography that makes up one element of the piece as a whole—are at once precise and overwhelming. Each photograph captures the house, in a different color, framed against a video screen backdrop that also changes color. That backdrop—technically speaking, a large LED video screen that was erected as part of this site-specific installation—teaches the eye to see this image like a work of art, to suddenly recategorize and re-contextualize this modest home (house) as a work of formal and visual argument. The clarity of the backdrop, covering up the extended landscape of emptiness where we can guess that houses used to be, brings the formal elements of the house itself into high relief. We see the articulated gable; the windows in various levels of pixelated clarity. In Dalison 4, in which the house is red and the background is blue, the shape is rendered almost Monopoly toy-like. The photograph brings to mind the scale of Playmobil, of a dollhouse. In other words, no life happened here. Dalison 1, meanwhile, shot at dusk and positioning the house against a brilliant white frame of a background, gestures towards all the life that happened here. The shades are drawn and yet the eye is drawn inward. What could have happened behind those doors? What kinds of mornings, days, night, occurred?

What is the value, some might ask, of making art about an object—a house, a place of so much hope and history—when that object is about to be destroyed? That question underlays so much of Strange’s work, which is at once deeply grieving and relentlessly optimistic. Strange’s photography reminds us that there is beauty to be found in acknowledging what is happening, in looking directly at this moment, as well as gesturing towards everything that might have once occurred off screen. It is rare to encounter art that at once stands on its own as an almost entirely aesthetic exercise—Strange’s photographs ask us to think about formal issues such as framing, color, exposure—and that invites us to think, as if beginning to unravel ourselves from inside our own memories and futures, about why this house, why now.

It’s compelling to look at heroic stories like this. Of this holdout family, the Cukrovs, one of few who refused to sell their house when more than 300 others agreed, who stayed and stayed and stayed. Under Strange’s generous, formal, thoughtful, and inventive approach, the family become more clearly rendered, even when absent, than they would with a touching, telling news piece.

What this work invites us to remember is that nothing is guaranteed, nothing is certain, nothing is ever safe. But while that might feel like a devastating blow, it can actually be comforting. If we’re never ever completely at home, if we can never reach this eternal security, we can still encounter moments of engagement, and connection, and deep warm memory along the way. Strange’s work reminds us that home is an idea that’s not only not fixed, it actually needs to be static for us to be able to comprehend it. 20 Dalison Avenue is a real place, as so achingly rendered by Strange. It also never was.

—

Eva Hagberg is an author, educator, academic with expertise in architectural history, history of art, American Studies, and material culture, and public speaker. She teaches in the Language and Thinking Program at Bard College and at the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation at Columbia University and holds a Ph.D: Visual and Narrative Culture from the University of California, Berkeley; an MS in Architecture from the University of California, Berkeley, and; an AB in Architecture from Princeton University. Her debut memoir, "How to be Loved", was published in February 2019 to overwhelming critical acclaim. Her architecture and design writing has appeared in the New York Times, Metropolis, Wallpaper*, and more. Her academic book, "When Eero Met His Match", is forthcoming Fall 2022 from Princeton University Press.

ARTICLE: 'Ian Strange’s Dalison'

by Cameron Bruhn

Originally published in Houses, June, 2022

ARTICLE: 'Ian Strange’s Dalison'

by Cameron Bruhn

Originally published in Houses, June, 2022

A beguiling, graphic and cinematic sensibility: Ian Strange’s ‘Dalison’

by Cameron Bruhn

There are compelling contradictions and complexities in the multidisciplinary artworks of Ian Strange. The Perth-born artist, who over the past decade has lived and worked in the USA and Australia, is known for his eerie explorations of domestic circumstances in crisis and decline. Strange depicts the darkness, disenfranchisement and disaster of emotionally and physically amplified living conditions with a beguiling, graphic and cinematic sensibility that simultaneously dislocates the viewer and monumentalizes the built artefact.

Strange returned to Perth in 2020 and spent the following two years working on Australian projects, including Dalison, a collaboration with acclaimed US musician and producer Trevor Powers. The site-specific performance work comprises a single-channel film, a four-part photographic series, a content-rich website and the short documentary “Making Dalison.” One of Strange’s most ambitious projects, this immersive, pulsating work has been realized at a time when the house has been the subject of unprecedented pressure: in the face of a global pandemic, the world’s populace rapidly shifted to working and learning from home, testing the limits of the domestic archetype and reimagining the suburban condition. Strange’s interpretive installation uses programmed theatre lighting and a stadium-sized video screen. This 260-square-metre scaffold, which functions as a giant green screen, enables Strange to confuse and augment the relationship between the building and its barren setting. “The idea of the project was to build this large-scale screen that would allow us to cut the house out of the landscape with light, to experience the home in shifting states of visibility, either silhouetted, isolated in darkness, or revealed in its vast, empty context,” says Strange. The atmospheric performance, which was documented over a period of three nights, is choreographed to Powers’ original 18-minute soundscape.

The hold-out house is a particularly fertile subject for Strange. He has engaged in a global study of these living conditions, generating thought-provoking works that probe the reasons people choose to stay in a house against all the odds – from the economic and political to the social and environmental. He observes, “In my work, I’m interested in universal and shared connections to the image of the home. These are places we tend to project with a sense of stability but are often more vulnerable and temporal than we would like to think. This is especially true in the experience of hold-out homeowners like those of 20 Dalison.” The beloved home of the Cukrov family for more than 60 years, the house – which will soon be demolished – is in the Perth township of Wattleup. The formerly vibrant suburb has been slowly subsumed by an industrial redevelopment that began in 1996, with more than 300 homes demolished and a corresponding destruction of community fabric and generational connections. In 2021, the abandoned number 20 Dalison Avenue and one other home were the last two remaining. Dalison thoughtfully pokes at the antagonism between the Australian home as an important site of memory and belonging, and the house as a realizable commodity that can be traded, developed and redeveloped.

With this work, Strange maturely signposts his place in the art of Australian suburbia after a sustained period of groundbreaking international practice. This national oeuvre includes the neon-powered blasts of Howard Arkley and John Brack’s broody depictions of the postwar optimism of the Australian suburbs. There is a prescient connection between Brack’s mid-century paintings of an emerging Australian suburbia and Strange’s most recent work. In works like Subdivision (1954), Brack drably depicts the scraped, bare earth of a newly cleared Australian landscape, freshly dotted with prosaic, brick-and-tile houses topped with pert, gable roofs. The houses that Brack enigmatically captured three-quarters of a century ago in their new-build state are the same ones that Strange depicts in his works. It is a disturbing tale of the rise and fall of suburbia, and Dalison is a powerful eulogy for a version of Australian life eviscerated by neoliberalism, consumerism and the seemingly unstoppable decline in housing affordability.

-

Professor Cameron Bruhn is the Dean and Head of School at The University of Queensland’s School of Architecture. Prior to this appointment, he was the editorial director of Architecture Media, where his role included the custodianship of the centenarian magazine Architecture Australia.

Bruhn holds a Bachelor of Architecture from the University of Queensland and a practice-based PhD from RMIT University. He was a co-creative director of the 2015 Australian Festival of Landscape Architecture: This Public Life and the 2016 Australian National Architecture conference: How Soon is Now. Bruhn is co-editor of The Forever House, The Terrace House and The Apartment House, books published by Thames and Hudson. His most recent project is MMXX,a landmark volume for Thames and Hudson that documents significant architecture in Australia in the first two decades of the twenty-first century.

Credits

DALISON was created as a collaboration between artist Ian Strange and musician Trevor Powers, it was produced by executive producer Jedda Andrews, creative producer Emma Pegrum, and co-director Dominic Pearce. This work would not have been possible without the generous support of Jim and Gary Cukrov, as well as the former residents of Wattleup who were involved in the making of this work. Detailed information on the project can be found at the dedicated project micro-site www.dalisonproject.com.

[FULL CREDITS]

ARTWORK & FILM-WORK

Artist/Co-Director: Ian Strange

Artist (Score): Trevor Powers

Co-Director/Editor: Dominic Pearce

Executive Producer: Jedda Andrews

Creative Producer: Emma Pegrum

Technical Producer: Paul Bilsby

Production/Site Manager: Matt Bairstow

Cinematographer: Daniel Craig (Matsu)

Lighting Designer: Riordan Hall-Jones

Camera Operator/Data Manager: Ben Berkhout

Camera Operator/Drone Operator: Dave Le May

Digital Imaging Technician: Joseph Landro

Sound Recordist: Jack Purkiss

Gaffer: Ed Martinez

Grip: Henry Richards

Grip/Gaffer Assistants: Joshua Robinson, Tana Glassock

Set Runners: Bailey Pascoe, Kaine Evans

Production Assistant: Taylor McCulloch

Head of Art Department: Steve Browne

Art Department Assistant: Lance Robinson

Graphic Design and Titles: Scott Mellor (Thinktank)

AV Supplier: Showscreens

House Modelling and Pre-Visualisation: Jamie Sher

Behind-the-Scenes Photography: Chris Gurney and Duncan Wright

Original Score: All music written, performed, and produced by Trevor Powers

Mixed by Jason Kingsland

Mastered by Heba Kadry

'MAKING DALISON' DOCUMENTARY

Co-Director: Dominic Pearce

Co-Director: Ian Strange

Producer/Writer/Story Editor: Emma Pegrum

Executive Producer: Jedda Andrews

Cinematography: Dominic Pearce and Daniel Craig (Perth, WA), Tyler Williams (Idaho)

Camera Operator/Data Manager: Ben Berkhout

Camera Operator/Drone Operator: Dave Le May

Sound Recordist: Jack Purkiss

Edited by: Steven Alyian and Dominic Pearce

Original Score (Making Dalison): Marc Earley

SPECIAL THANKS

The artists and producers wish to thank Jim and Gary Cukrov, as well as the former residents of Wattleup who were involved in the making of this work.

This work would not be possible without the generous support of a number of individuals and organisations. Ian Strange and the producers extend a sincere thank you to Paul, Sophie, Holly and Katie Chamberlain; Nik Rogers; Adrian and Michela Fini; Nicky Coxon and Brent Rogers; Darryl Mack and Helen Taylor; Caroline Christie-Coxon; Tim, Chris and Maddie Unger; Graeme and Eva Morgan; Kamilė Burinskaitė; Al Taylor; Nathan Benett; Kyle Jeavons; Luke McKinnon; Miles Plumlee; Matt Murphy; Melissa and David Alder, and; Graeme and Iris Morgan. For their incredible support and collaboration, we also thank Bryce Varley at Showscreens; David Revill at TAFE WA; Tiki Menegola; Development WA; the City of Cockburn; Western Power, and; Patrick Abromeit at the Department of Transport.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF COUNTRY

The artists and producers of this work acknowledge the unceded lands upon which it is created, and from which we work. We acknowledge the Bunurong Boon Wurrung and Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung peoples of the Eastern Kulin Nation, the Traditional Owners of the land on which Ian Strange Studio operates in Naarm (Melbourne). DALISON was created on the traditional land of the Beeliar people of the Whadjuk Noongar clan. While this work explores social displacement occurring in the late 20th century, we acknowledge that the Beeliar Noongar people were violently dispossessed and displaced by colonisation before this, and that the ongoing impacts of colonisation, such as systemic racism, persist. We pay respect to First Nations Peoples as the first artists and storytellers to walk this Country and acknowledge their continuing connection to land, waters and culture.

[Selected Press]

Sydney Morning Herald, February 26, 2022

Haunting artwork evokes the neighbourhood that didn’t need to disappear. This article was first published in Spectrum, The Age, and also appeared in The Age, Brisbane Times and WA Today.

The West Australian, February 28, 2022

Perth artist Ian Strange’s Dalison project sheds light on the David and Goliath battle for suburban home

Monster Children, February, 2022

Ian Strange Explores the Suburb that Western Australia Forgot

ABC News, March 2, 2022

Old family home gets dramatic demolition send-off in artistic installation by Ian Strange

Design Boom, March 2, 2022

Ian Strange & Trevor Powers to release short film as eulogy for isolated Australian house

HYPEBEAST, March 3, 2022

Ian Strange collaborates with Trevor Powers on 'Dalison'

Broadsheet, March 4, 2022

A Major New Work by Artist Ian Strange Is a Eulogy to a Lost Suburb and the Impermanence of Home

ICON, March 15, 2022

Ian Strange and Trevor Powers collaborate on new film and photographic series Dalison

ABC Radio National, The Art Show, March 30, 2022

Home Truths: Ian Strange. Interview duration: 24minutes (06:35-30:45) Also available on Apple Podcasts, and Google Podcasts

Artshub, May 23, 2022

☆☆☆☆☆ A short-film collaborative eulogy about a dying Australian house is also a celebration of home.

NuArt Journal, Issue 6, 2022

Dalison: A Visual-Sonic Collaboration (pg102–120)

HOUSES, July 15, 2022

A beguiling, graphic and cinematic sensibility: Ian Strange's 'Dalison'